Major League Baseball now faces the same challenge the NFL has long struggled to meet. MLB’s new policy on domestic abuse is being tested for the first time this offseason, and it’s being watched closely because of the failings of the NFL’s initial policy.

Right out of the gate, the new MLB policy is being tested in ways that would have been hard to predict. MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has already shown the wherewithal to learn from Roger Goodell’s mistakes without repeating them – a trend he’ll need to continue as he navigates new waters and an ever-changing social and cultural landscape.

Currently there are three MLB domestic abuse investigations underway. Former Toronto Blue Jay Jose Reyes is facing criminal charges in Maui for allegedly assaulting and injuring his wife at the end of October.

Yasiel Puig was not arrested but it is alleged he had a physical altercation with his sister at a Miami bar. There are contradicting reports that the fight was in fact with a bouncer and he did not shove his sister. If so the case would be detrimental conduct, but not domestic abuse.

The most complex case is that of Aroldis Chapman, who was to be traded from the Cincinnati Reds to the Los Angeles Dodgers before reports of a domestic incident surfaced. Chapman’s case is not being criminally prosecuted because of a lack of evidence and conflicting reports. The left-hander’s girlfriend said he pushed her and choked her, and Chapman admitted in a police report that he fired eight shots of a handgun in his garage. He claims he was alone and that a cut on his hand was from punching the airbag in his car. His girlfriend was found hiding in the bushes when police arrived. The ramifications of the new policy have taken arguably the most significant trade in the offseason and put it at least on hold, possibly squashed it for good.

The rulings in these cases will be closely watched and scrutinized, as there is no precedent. In these cases the commissioner has wide-open jurisdiction. Since there are no mandatory minimum and maximum disciplines, these cases are setting the precedent for future cases so there is pressure to get this right.

Terms of joint domestic violence policy

“The Commissioner shall have authority to discipline a player who commits an act of domestic violence, sexual assault or child abuse for just cause. There is no minimum or maximum penalty prescribed under the policy, but rather the Commissioner can issue the discipline he believes is appropriate in light of the severity of the conduct. The Commissioner’s authority to discipline is not dependent on whether the player is convicted or pleads guilty to a crime.”

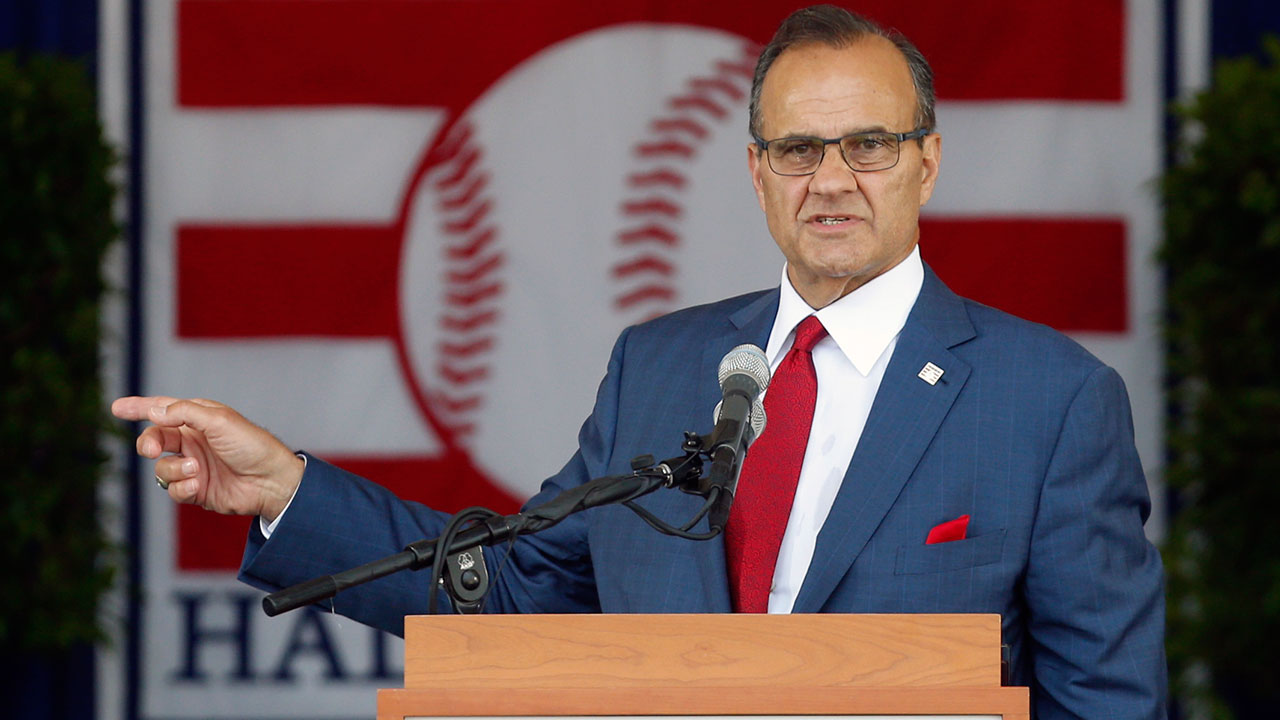

MLB chief baseball officer Joe Torre, who is overseeing the league’s investigations, has been vocal about the fact that MLB isn’t taking these sorts of cases lightly.

“There is no grass growing under anybody’s feet here,” Torre said. “I’m proud of the fact Major League Baseball came up with the policy because it’s too important of an issue not to pay attention to it.”

Torre’s role from an optics point of view is an important one as he’s been outspoken in the past about growing up in an abusive household.

Public relations — a huge element of these cases — has been the NFL’s continued Achilles heel. The topic already put a cloud over the MLB off-season. Instead of talking exclusively about trades and free agency, questions about legal cases arose.

At the Winter Meetings, Washington Nationals manager Dusty Baker’s glowing character reference of the accused relief pitcher only incited more discourse. “He’s a heck of a guy. I mean a heck of a guy. I’ll go on record and say I wouldn’t mind having Chappy,” Baker said of Chapman.

Baker later added: “I think this policy needs to go further to whoever is involved. Sometimes the abuser doesn’t always have pants on.”

Those comments were perceived as victim blaming, something the NFL was accused of when they interviewed Ray Rice’s partner Janay Palmer in front of her assailant and his bosses. As if that wasn’t bad enough, they later had her participate in a press conference at which she said she regretted her actions.

Baker was actually trying to convey what happened to one of his former players, and alluded to former MLB outfielder Darryl Hamilton, who was killed by his girlfriend. The comments were perceived as insensitive and ill-timed. Baker then clarified his words, saying, “You have to wait to see what happened. I’m not one to judge prematurely.”

Even if Baker’s comments were lost in translation, this is the type of public condemnation MLB is looking to avoid. Dusty Baker wasn’t working in the league when they instituted team-by-team education programs earlier this year. The public discourse he started showed just the importance of having a comprehensive policy including sensitivity and media training.

The biggest thing the MLB has gotten right where the NFL failed is the realization that an attack of this issue is a joint venture. The policy was negotiated with the MLBPA and formalized in August. Because of mounting public pressure, the NFL made changes to their policy that were not collectively bargained.

Another distinction between the NFL and MLB policies is the role of investigations in the appeals process. In the NFL the commissioner is the judge, jury, and executioner. Goodell has the power to act as his own arbitrator, but Manfred will have to defer to a three-person arbitration panel consisting of a player representative, a league representative and a neutral third party. It is a smart decision by MLB considering that Goodell has come under fire for ruling with an iron fist. It is also a testament to the MLBPA’s bargaining power in comparison to the NFLPA.

In the last year, the relationship between the NFL commissioner’s office and the NFLPA has become even more contentious. Each of the NFL’s conduct policy decisions has been appealed, and not only the findings but the investigation process itself. The greater downfall for the league is that stories stay in the news longer and impact business more as cases drag on.

Baseball will have appeals, but there is an agreement on the goals they are working towards and how appeals should be heard. Manfred’s comments after the Reyes news show his intentions for the policy.

“The key from our perspective was being proactive and negotiating what we see as a comprehensive policy with the MLBPA so everybody knows how the process is going to work,” Manfred said. “The second word I’d like to emphasize is comprehensive. This is not just a discipline policy. It is a policy that requires evaluation, counselling, a variety of other activities in addition to the disciplinary competent.”

The comprehensive portion might be more valuable than the discipline. Three experts will chair a joint policy board tasked with developing a treatment plan. The confidential treatment could included mandatory counselling and psychological evaluations. Players who do not comply are open to further punishment from the commissioner.

All three of the players under investigation are Latin American, and two of them defected. The comprehensive portion of the policy needs to address cultural factors and aim to educate, instead of simply punishing those who make mistakes.

The league must also determine when and how teams should share information about domestic incidents. According to a report in the Boston Globe, the Red Sox knew about Chapman’s issue before it was widely reported, which is why they traded for Craig Kimbrel instead.

It is customary for MLB clubs investigate character and background before they make big deals. However, it is not customary for them to disclose their findings.

The Kimbrel trade was completed weeks ago. At that point did they have a responsibility to disclose their findings to the league? Are Dave Dombrowski and the Red Sox liable if this is a joint venture and the thirty clubs are all partners? Should the opposite be true? Does MLB have an obligation to inform clubs about the status of players under investigation? Before the Chapman trade is deemed officially dead the Dodgers have to gather information from MLB to decide if it it’s worth the public relations risk.

Should MLB disclose information during a working investigation? Is that unfair to the Reds who thought they had a deal?

If Chapman is suspended for more than 46 games, he’ll lose enough service time and that he would no longer be eligible for free agency after the upcoming season. The fact that a suspension would buy Andrew Friedman and the Dodgers another season of Chapman before he hits free agency may actually gives the Dodgers more incentive to make the deal.

The Chapman case is tricky because the police report has conflicting facts, and thus the prosecution has dropped the case. The state of Florida, where the incident took place, has very liberal gun laws, though it’s entirely possible the case would be tried elsewhere.

By separating his decision from the legal process, Manfred gives himself the ability to keep an even playing field in terms of executing discipline on cases that occur in different marketplaces. MLB discipline is not dependent on a criminal conviction, but the commissioner reserves the right to defer his decision until criminal cases are resolved which avoids the awkward position the NFL has been in where they were convicting players before the legal proceedings had concluded.

The other grey area is what do you do with potential offenders in-season, since it’s awkward to have them on the field representing the league amidst controversy. The NFL wasn’t prepared for the media and fanbase to be so disgusted with alleged felons playing in primetime. They adopted the practice of putting players like Greg Hardy on the Commissioner’s Exempt List for however long Goodell needed before ruling.

MLB has a provision stating that players can be suspended with pay while criminal charges are pending if the commissioner determines that “allowing the player to play during the pendency of the criminal or legal proceeding would result in substantial or irreparable harm to either the club or Major League Baseball.”

The NFL made its share of mistakes but unlike MLB had no other organization’s experience to draw from. It’s not as if this is a football-specific problem. It’s a societal problem the NFL was forced to deal with first. You can argue that MLB has a greater issue than the NFL.

Manfred is on the right track to date by resisting the urge to rush the Puig decision before he went to Cuba to represent Major League Baseball on a three-day goodwill tour.

The MLB constitution has been around since 1875 and yet the league only recently created a domestic abuse policy. It now exists because football has a policy and any league without one risks falling behind.

MLB’s existing policy has benefited from the NFL’s ongoing challenges but also leaves room for MLB to be agile — a necessity considering that education on and interpretation of domestic abuse is fluid. Robert Manfred, you’re on the clock.