TORONTO – During Brook Jacoby’s playing days in the 1980s, getting into an advantage count as a hitter automatically meant sitting dead red and gearing up for the fastball. And almost inevitably, as if on schedule, a challenge heater in a meaty part of the zone would come.

“Guys would throw you something off-speed now and then, but most guys were going to go after you in those counts and go after you with a fastball,” says the Toronto Blue Jays hitting coach, who was a two-time all-star and posted a .739 OPS over parts of 11 big-league seasons. “The game has changed in that respect. Pitchers are relying more on their breaking stuff, pitching backwards.

Usually it was a change-up, you’d get a change-up in a fastball count. Now guys are throwing everything in those counts.”

Today’s pitchers are very much doing precisely that, to the point that a growing number of players on the mound and in the batter’s box feel that the traditional fastball count is disappearing, and hitters more than ever need to be ready for any pitch at any time.

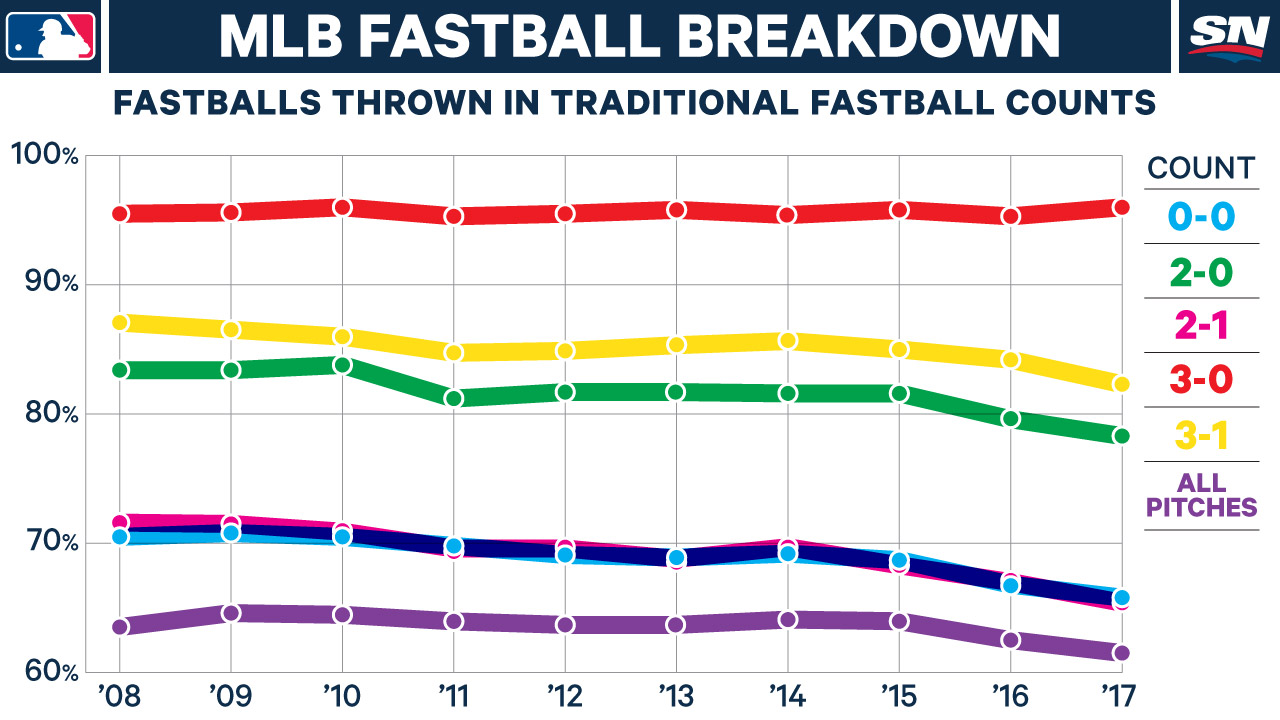

A review of Pitch F/X data from 2008-16 and Statcast information from this season underlines that fact, as the overall use of off-speed pitches has increased by two per cent over the past decade, but risen by about five per cent in 2-0, 2-1 and 3-1 counts.

Fastball usage is also down about five per cent in the first pitch of an at-bat, with the pace of change picking up since the 2015 season. It’s too early to determine whether this is a definitive shift or a cyclical trend, but both anecdotally and empirically, pitchers are changing the way they attack when they fall behind in the count.

“There’s really no such thing as hitters’ counts per se as far as a 2-1 heater or a 3-1 heater, especially in the American League East. There are a lot of wrinkles in there,” says Blue Jays slugger Josh Donaldson. “You have to be disciplined. You have to be really focused in on what you’re trying to accomplish, you have to be ready for any type of mistake, not just a fastball mistake or whatnot.

“It makes you have to be a more disciplined hitter.”

[snippet id=3526033]

There are a number of possible explanations for the shift in pitch selection during leverage counts, but Blue Jays pitching coach Pete Walker points to the most obvious one.

“Breaking balls are just better,” he says. “I think it’s the philosophy of certain organizations that they use more breaking stuff and incorporating them in fastball counts. But it may also be an indication of guys utilizing their strengths a little more. It’s not necessarily something we’re looking to do but there are certain guys with plus breaking stuff that they’re not afraid to throw in certain counts, that’s for sure.”

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 (through Aug. 14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-0 Count | 70.50% | 70.80% | 70.50% | 69.80% | 69.10% | 68.90% | 69.20% | 68.70% | 66.80% | 65.80% |

| 2-0 Count | 83.40% | 83.40% | 83.80% | 81.20% | 81.70% | 81.70% | 81.60% | 81.60% | 79.60% | 78.30% |

| 2-1 Count | 71.60% | 71.50% | 70.90% | 69.60% | 69.60% | 68.80% | 69.70% | 68.30% | 67.00% | 65.40% |

| 3-0 Count | 95.50% | 95.60% | 96.00% | 95.30% | 95.50% | 95.80% | 95.40% | 95.80% | 95.30% | 96.00% |

| 3-1 Count | 87.08% | 86.53% | 85.99% | 84.74% | 84.89% | 85.33% | 85.65% | 85.00% | 84.20% | 82.31% |

| All Pitches | 63.52% | 64.60% | 64.47% | 63.96% | 63.69% | 63.69% | 64.10% | 63.97% | 62.51% | 61.51% |

Blue Jays slugger Jose Bautista agrees breaking balls are better, but he makes the distinction that they’re not any nastier in terms of break or movement, but in the ability of pitchers to more regularly throw them for strikes.

That development, he argues, is substantial because hitters up in counts used to confidently be able to let a pitch go if they identified spin without fear of losing control in the at-bat. No more.

“You can still lay off it because that’s not what you want to hunt for but that breaking ball might go for a strike and that changes the dynamic of the at-bat,” he says. “It doesn’t necessarily bring (the advantage) back to the pitcher right away, but it does make you as a hitter more protective of the strike zone because you can’t wipe it as a possibility.”

Another factor, J.A. Happ argues, is that the surge in home runs across the majors is prompting pitchers to rethink their strategies. Through Aug. 30, there were 5,014 longballs in 3,944 games, compared to 5,610 in 4,856 games last year. In 2015, there were 4,909 homers in 4,858 games.

“The traditional fastball or off-speed counts are non-existent anymore with the balls going out of the ballpark the way they are,” says Happ. “Obviously you’ve got to try to make a good pitch, even if you’re going to go off-speed, but it seems like hitters more and more, aren’t expecting, but are more used to seeing that.”

Marcus Stroman agrees with his rotation-mate and goes a step further, arguing that pitching backwards at times is crucial to success, particularly as the tolerance for strikeouts has risen, allowing hitters to load up for bigger and bigger swings.

“Essentially, what are hitters looking for 2-0, 3-1?” says Stroman. “They’re doing everything they can (to) time up a fastball with their big leg kicks. They’re unbelievable athletes these days, they don’t have to square it up to hit a homer, know what I mean? So a 2-0 count, 3-1 count comes, and you’re a pitcher, you’re not grooving this guy a heater. If you have the feel for (an off-speed pitch), I’m a 100 per cent for it.”

Bautista believes the increase in strikeouts around baseball and the way bullpens are used factor in, as well. There’s an emphasis on getting swings and misses now, even when a pitcher is behind in the count.

“The extended use of bullpens, hybrid relievers like Andrew Miller who come in earlier in the game and handle situations, and how often people get called up and down between triple-A and the big leagues because of fatigue or overuse of the bullpen, allow pitchers to have that type of approach,” he says. “Before, they might be more inclined to throw fastballs to keep their pitch counts down and get quick outs with contact, inducing a weak ground ball or a pop up. I feel like a lot of people are pitching toward the strikeout instead of just getting outs.”

[relatedlinks]

Russell Martin has been on both sides of the shift, calling for his pitchers to throw more off-speed offerings in traditional fastball counts, and trying to deal with the element of surprise at the plate. He praises former Blue Jays teammate Edwin Encarnacion as the hitter best able to adapt from hard to soft.

“They’d groove some off-speed pitch in an advantage count for the hitter, and Eddie would sit on it and square it up,” he says.

Still, the veteran catcher believes the key is in understanding a pitcher’s tendencies and then developing a plan of attack with those numbers in mind.

“I like hitting the fastball but over the years I’ve realized you’re not always going to get what you want to get,” says Martin. “I’d rather get on a pitch you can expect to get instead of waiting on a pitch you’re never going to get. So I have changed a little bit, I probably sit off-speed a little bit more than I used to but it doesn’t always work out. Sometimes you get that fastball right down the middle and it’s like, golly, there it is. You gamble sometimes and sometimes you guess right and sometimes you don’t.”

Stroman has spent time studying many of the game’s top pitchers, and what he’s noticed is that those who aren’t overly fastball reliant tend to have more success because they simply have more weapons to work with.

“That’s the game of baseball, to have that chess battle between pitcher and hitter,” says Stroman. “Obviously you want to throw them off, you don’t want to give them what they want. Guys want heaters. And if you look at the elite pitchers, they throw a lot of off-speed. Clayton Kershaw, serious mix. Corey Kluber, serious mix. These guys have their sliders, their curveballs they can go to get guys off the heater.”

Between his four-seamer and his two-seamer, Happ is at about 71 per cent fastball usage this season and when things get hairy, those are the offerings he tends to fall back on. He believes that pitchers are best off pitching to their strengths rather than trying to mix things up for the sake of it.

“But there are certainly times when it’s like, ‘Hey, I’m behind this guy, I’m going to try to execute with a pitch he doesn’t expect,’” he says. “That’s the name of the game, always, but especially when you’re behind in the count.”

Adds Martin: “It’s what pitching is. Either you make a pitch in the right location, the guy’s on it but you make a good pitch, or you fool him. They can both work. That’s the art of the game right there, that’s exactly it. There are times when you challenge, and there are times when you trick a guy.”

Increasingly, hitters must contend with less of the former, and more of the latter.