Back in the spring of 2002 I was sitting next to Shawn Simpson, then a scout for the Washington Capitals, watching a game at the world under-18 championships. At some point in a forgettable game, another scout approached Simpson and said, cryptically: “It sort of takes you back.”

For a moment I didn’t get it.

“What’s that about?” I said.

“The fight.”

The wheels were turning slowly and then I put it together. We were sitting in the Zimny Stadion in Piestany, Slovakia. This was the site of the 1987 world junior championship, site of probably the most famous and certainly the most infamous moment in the history of the WJC.

Back in ’87, Canada and the USSR met in the tournament’s final game. According to the IIHF’s record books, the game was never played and the two teams never even made it to Piestany. The Canadian and Soviet teens engaged in a bench-clearing melee that wasn’t ended by either officials shutting down the lights or soldiers coming out onto the ice with guns and dogs—the on-ice officials simply left in the middle of it. Leading them in this retreat was referee Hans Ronning, an over-matched Norwegian ref who was working in his first game of this magnitude and his last game at any level. The only thing that put the fight to an end was pure exhaustion, and in the aftermath the guys in the blazers punted both teams out of the tournament.

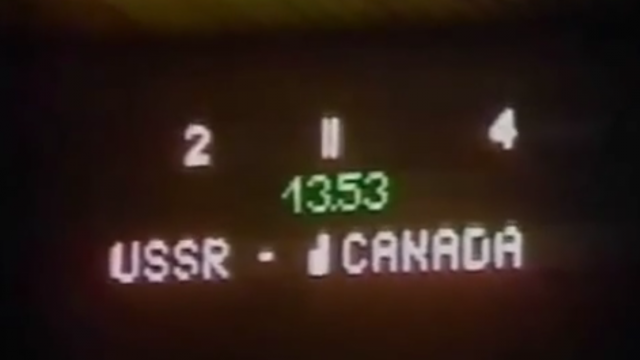

The WJC followed a round-robin format back in those days. Going into the game, Canada needed a clear win for a gold but was guaranteed a bronze even with a loss. They were leading the Russians 4–2 but wound up not even credited with a defeat. No medal whatsoever.

Shawn Simpson was centre stage in the melee. He was the back-up goaltender and squared up with the Soviets’ back-up, one Vadim Privalov. A natural welterweight, Simpson was giving away at least 40 lb. to Privalov, maybe more. Nonetheless, in antic fashion, Simpson pinned him to the ice and wailed away. He had started out the tournament as the No. 1 goalie for Canada, suffered an injury that put him on the bench and took out his frustrations on Privalov at centre ice.

Watching the 2002 under-18 tournament, I asked Simpson how often people asked about that game and that fight.

“Every day,” he said. His words were faintly redolent of resignation.

It was at that moment I knew I had to write a book about it. It took a few years for me to find a publisher who shared my opinion but eventually one did, that being Doubleday Canada. That book, When the Lights Went Out: How One Brawl Ended Hockey’s Cold War and Changed the Game, came out in the fall of 2006 and you might be able to find a copy of it. (This is not a shameless for-profit plug. Even if it sold by the boxload tomorrow, I will never see another dollar from the book.)

I spent months working on that book. I chased players from both teams, and got all but a couple of Canadians, most of the Russians, IIHF officials including the Norwegian ref and eyewitnesses. The Canadian forward line on the ice at the time was fairly representative of the myriad directions I had to go to find the stories behind the stories.

I found Theoren Fleury in Belfast where he was playing for a team in the British league. In the afternoon Fleury told me that he could help Canada’s team at the Olympics in Turin, and that night he was tossed from a game and threw the entire stick-rack on the ice in protest. I found Mike Keane hanging on at a slightly higher level, playing for the Manitoba Moose in the AHL. He’d accepted the fact that he wasn’t making it back to the NHL but not the idea that he should walk away from the game. I found Everett Sanipass on a reserve in New Brunswick where his role in the infamous brawl gave him a measure of enduring celebrity far beyond his 11 NHL games with the Chicago Blackhawks.

I get asked about that game—not as often as Simpson but more often than any game I covered live. At one point I was approached about developing the book into a TV movie and—my hand on a Bible—the producer was the brains behind Trailer Park Boys. But just as the Canadians went home without a medal, I went home without a broadcast-royalty cheque.

I was recently asked by a reporter in Montreal if I thought a fight like the one in Piestany could ever happen again.

“If you have to ask,” I said, “you have your answer.”

No, we’re not going to see a bench-clearing brawl at the WJC again. And the fact is we’d never seen it before the Canada-USSR game in the former Czechoslovakia.

It’s hard for younger hockey fans to process the idea (and it requires visiting long-closed corridors of the memory bank for those in their 50s and 60s) but the culture of the game was very different three decades ago. Back in the ’70s, you’d go to a Flyers game and come away disappointed if there wasn’t at least a line brawl. Looking through old newspaper clippings in advance of the ’87 WJC, I found a story of a game between the Oshawa Generals and Peterborough Petes. The bench-clearing brawl in that game was mentioned for the first time in the 16th paragraph and the coaches coming to blows was not much more than a footnote.

A few weeks later two of the Petes, Kerry Huffman and the late Steve Chiasson, would be dropping their gloves and looking for the nearest Soviets in Piestany.

Fighting in hockey is on the way out today but the place of fighting in the game today in no way resembles what it was in ’87. In fact, Piestany was not just the nadir but a last gasp—within a couple of years the NHL and major-junior leagues effectively legislated bench-clearings out of existence. To whatever degree, back in ’87 virtually everyone could fight, and many actively looked to do it. These days it’s down to a dwindling few.

Of course the impossibility of Piestany 2.0 goes far beyond the culture of the game. The world was a very different place. The game was played in a now-extinct nation then under the sphere of Soviet influence. The Canadians were playing against a team they knew nothing about, that they had never seen before. To them, the Soviets were simply the hated enemy, Cold War villains, those on the other side of the Wall.

The Soviets regarded the Canadians pretty much the same way, although they had to envy the fact that their opponents would have a chance to play in the NHL while the best any of them could hope for was a spot on the Red Army roster. If you’d told any of the guys in the Canadian lineup that they’d one day be teammates with any of the Soviets you’d have drawn a blank look. If you told any of those on the Soviet team that they’d someday play in the NHL, maybe it would register with Alexander Mogilny and Sergei Fedorov, but for others it would be pure fantasy. There was an otherness that’s long gone.

Now you’ll see Russian teams on tour every season. You’ll see them at the under-17s. You’ll see them at the Quebec peewee tournament. And some Russians will have their rights assigned to the same NHL teams as the Canadians. They’ll share the same agents. However divided the real world remains, there’s really one hockey world now and the players of all nations share in it.

To this day, the most frequent question of all remains the same: How did the brawl in Piestany happen? It was what it had to be—a perfect storm.

The teams’ situations—all and nothing, respectively—impacted it, of course. Canada needing nothing less than a win for a gold. The Soviets had no shot at a medal, nothing to lose, not even a measure of pride to reclaim. A few matters of dispute remain. Did the Soviet coach send his players off the bench and over the boards when the line brawl with Fleury, Keane and Sanipass boiled over? Possibly, maybe probably. Who was the first to go? A matter of some dispute, but the likeliest candidate was Evgeny Davydov, who had a limited NHL career and no rep at all as a tough guy. Did coach Bert Templeton and his assistant, Pat Burns, lose control of the Canadian team or throw gasoline on the fire? I’m not going to speak ill of the dead but having talked to both over the years and to others who knew them well, Piestany always haunted Templeton, a career junior coach, but Burns was able to move well past it to the Stanley Cup and Hockey Hall of Fame.

I conducted more than 100 interviews for When the Lights Went Out and only one principal told me he thought the brawl could have been avoided, but he was entirely credible: Peter Pomoell, a veteran Finnish linesman who worked that game in Piestany. He maintained events would have played out very differently if the IIHF had selected a referee other than Hans Ronning, who had been handpicked by the IIHF’s head of officiating, Rene Faisel, now the federation’s president.

Pomoell told me that he knew they were sitting on a powder keg but Ronning seemed oblivious to the danger ahead.

“If Ronning had spoken to the captains and coaches before the game or during the game… maybe it could have been avoided,” Pomoell said. “I asked him before the game, ‘Do you want my help on calls—majors, misconducts?’ He said no. I asked all referees this. I worked six world championships, lots of world junior and international games. Canada versus the Soviets… those two teams produced the best hockey, but they were also the toughest games to work. I knew this, maybe Ronning didn’t. He refused my help. Maybe it was pride… he might have thought that I was telling him that he wasn’t good enough or that he wasn’t ready. Maybe it was the fact that he was working in front of the IIHF executives and the supervisor of the [on-ice] officials.

“I had a bad feeling even before the game. I thought something bad could happen—just the situation of one team having nothing to play for and a big rivalry… the way that this Canadian team was playing, very rough, big hits, intimidating hockey. But I had a worse feeling once the game started. Right away on the first face-off you can see a big cross-check. The puck hit the ice and the Canadian player cross-checks a Soviet. Ronning didn’t make a call. He didn’t miss it—he saw it, it happened right in front of him…. He just never made a move for his whistle. And that’s how it was that whole first period. I don’t know that he called many in the first 20 minutes.”

Pomoell said that Ronning was crestfallen in the officials’ dressing room.

“He was unable to speak,” Pomoell said. “He was devastated. He wasn’t crying… more in shock. Then Rene Faisel came in and he is shouting. He’s outraged at Ronning.”

Pomoell stayed involved in Finnish and international hockey on and off the ice for two decades after Piestany. He told me he spoke to Ronning after the 1987 WJC.

“I’ve never heard from him,” Pomoell said. “He never refereed another game. He was broken by it. Nobody knows where he is.”

So it seemed. I spoke to members of the Norwegian hockey federation and none of them even knew of Hans Ronning. No Hans Ronnings were listed in the national phone directory. As it turned out there were seven Hans Ronnings in Norway and I tracked down six of them before finding the ref from Piestany. Ronning disputed Pomoell’s version of events.

“The linesman doesn’t have it quite right. I didn’t referee another game internationally,” he said. “I did referee another two seasons in Norway. In Piestany I was 38 years old. I only had a couple of years left. I thought that this tournament was probably going to be my last or one of my last international [assignments].”

Ronning blamed the coaches and the players.

“It is the coaches’ responsibility to have team discipline in place,” Ronning said. “The coaches should have kept their players on the bench. And they should have told the players on the ice not to fight… or to stop fighting. I think that maybe this could only happen with teenagers. Professionals have discipline and they know what is their job—some things they will not risk. What the players did was not a mature decision but a reaction—impulse is the word. They were innocents under a lot of pressure. They can be blamed but not too much.”

Ronning also had a view shared by no one and in complete contradiction of video evidence.

“It was the Canadians who left the bench first,” he said. “It was their fault that the fight happened. They started it. And I have no idea why when they still had a chance at the gold medal.”

Ronning accepted no blame for the brawl in Piestany.

“When it is just the players on the ice, then it should be in my hands,” Ronning says. “But when the benches clear, it’s in God’s hands. There is nothing that three officials can really do. We stayed on the ice for several minutes. We tried to do what we could with the fights that were going on. But really there was nothing that could be done by us when the benches cleared.”

I wasn’t surprised when Ronning told me that he had never talked about the brawl in Piestany until I had called almost two full decades after the fact. I didn’t bother to tell him that Shawn Simpson had to talk about it every day. Ronning didn’t deserve to get off easy but did. Simpson and so many others weren’t as lucky, but at least he could manage to laugh about it.