The shootout arrived at the NHL level in the summer of 2005 as the most distinctive in a slate of rule changes designed to appeal to disheartened fans after a season lost to a labour dispute. Long a staple of international hockey, it was designed to replace the dissatisfaction of a tie game with the thrill of a breakaway contest.

It was a dramatic shift by a league that prefers evolution to revolution of the rulebook, and ever since its adoption there have been prominent hockey men fighting a rearguard action to limit its presence. The latest example is the recommendation from NHL general managers to move to a 3-on-3 overtime format.

The NHL’s official announcement of the recommendation was carefully worded; without context one would almost think that the shootout enjoyed great popularity among the league’s decision makers.

Commissioner Gary Bettman described an overwhelming consensus in the room in favour of keeping the shootout. Detroit Red Wings GM Ken Holland, who has long been a prominent force behind reforming the league’s overtime format, proclaimed that he and his peers still wanted shootouts in the game and that they believed fans like shootouts. Both stressed that this format was simply designed to put a little more emphasis on overtime rather than the shootout.

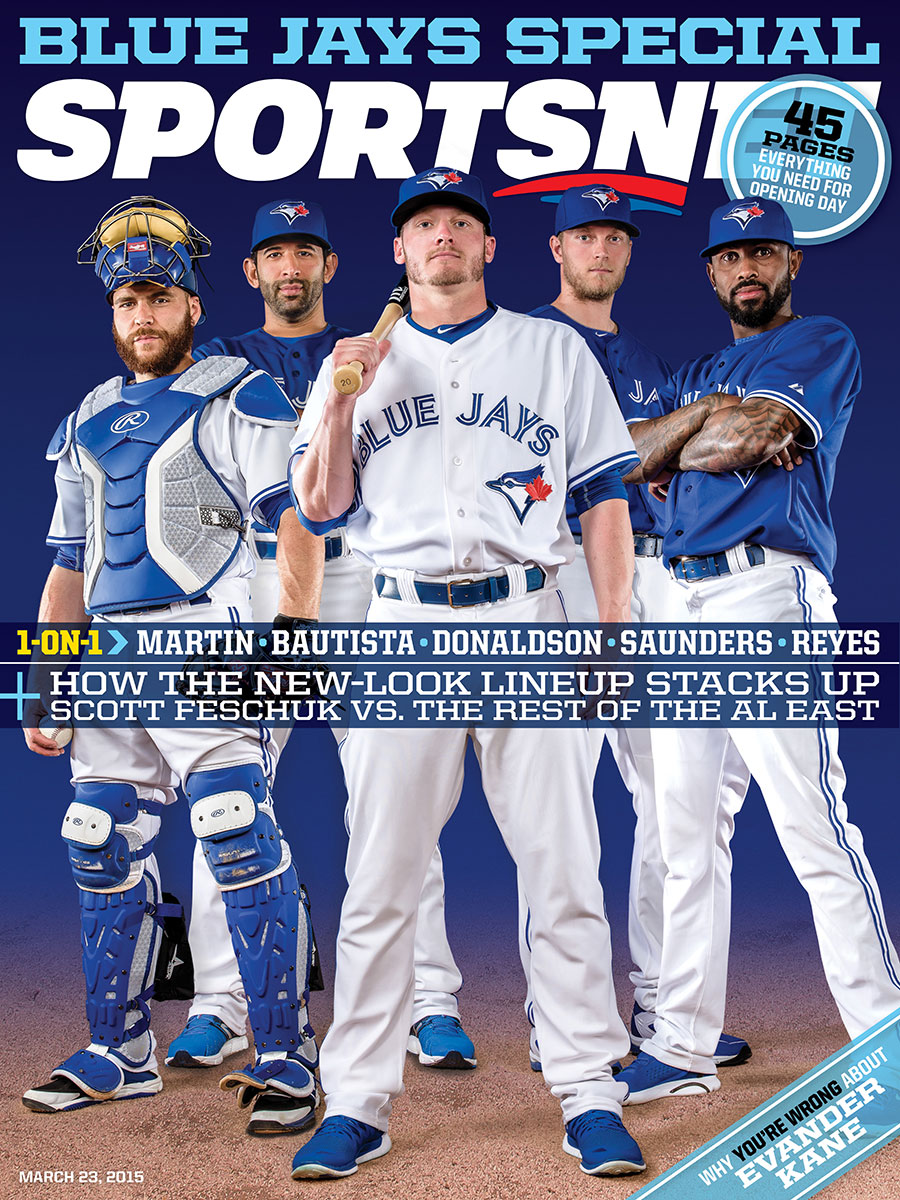

Sportsnet Magazine’s Toronto

Sportsnet Magazine’s Toronto

Blue Jays Special: From the heart of the order to the bottom of the bullpen, we’ve got this team covered in our preview issue. Download it right now on your iOS or Android device, free to Sportsnet ONE subscribers.

But in other moments, leading executives from the hockey side have been decidedly more candid on their views.

Nashville Predators GM David Poile has made the same “the fans like it” argument that Holland did, but acknowledged that as a hockey man he liked “to see the game end by a goal versus a shootout.” Calgary Flames president Brian Burke, in his customary style, last year declared shootouts to be “horse s–t” and “a circus stunt.”

In December Holland’s colleague in Detroit, Jim Devellano, made it clear that the goal of reforming overtime was “to eliminate a good portion of the shootouts.”

This isn’t just the dissatisfaction of an unhappy old guard that would rally against any rule change of any kind. The problem with the shootout is that it is essentially a random element added at the end of the game that isn’t generally decided by skill.

“[T]he NHL Shootout is a crapshoot,” is how Michael Shuckers, an associate professor of statistics at St. Lawrence University put it in a blog post. “Put more statistically, there is not enough evidence to suggest that individual skill levels make a difference in player shootout performance… that among [the most-used] players any one is better than another at the shootout.”

Understandably, hockey men prefer not to add uncertainty to an uncertain game. Poile had to fire long-time Predators coach Barry Trotz after a disappointing season in which Nashville missed the playoffs and, according to a rumour, came close to being fired himself. There were lots of reasons; one of them was a 2-9 record in the shootout in a season in which his team missed the playoffs by three points.

This year the Preds are 6-5 in shootouts and it’s hard not to wonder if Trotz would still be employed by Nashville if that had been the case last year (not that the parting of ways has worked out all that badly for Trotz or the Predators).

But while 3-on-3 overtime will help, it’s not a solution in and of itself because there’s still massive incentive for teams to go to overtime. The NHL system is structured so that there are two points available to be handed out to the teams involved in a game decided in regulation; there are three available in overtime/shootout games.

So when the game is tied with 10 minutes left in the third period, both teams have an incentive to play low-event, defensive hockey the rest of the way to ensure that they at least collect a point. In a league that is constantly combating a tendency toward low-scoring games, the very structure of the scoring system encourages them.

Holland pointed to the Swedish Hockey League as an example of the merits of three-on-three overtime, telling NHL.com that the league went from roughly 38 percent of its games being decided in overtime rather than the shootout to something in the 75-80 percent range.

What he didn’t point out was that the SHL operates under a very different point system than the NHL does—three points awarded for a regulation win, two for an overtime/shootout win, one for an overtime/shootout loss and none for a regulation loss. The same number of points is available in every game; no extra point magically appears for managing to make it to overtime.

A team that plays defensive hockey still guarantees itself a point, but in so doing it also guarantees the sacrifice of a point to its opponent. The incentive is to do everything at all points to win.

The Swedes instituted the three-point system in the late 1990s and saw an immediate five percent bump in scoring. The NHL of the same era watched scoring fall for half a decade before the rule changes and power plays of 2005-06 briefly reversed the low-scoring trend.

None of this is to say that 3-on-3 overtime is a bad idea. On the contrary, making overtime more decisive is one way to lessen the corrupting impact of the shootout on the NHL standings. It simply isn’t enough; the NHL also needs to remove the obvious incentive that every team in the NHL has to force games to overtime. A 3-on-3 overtime in concert with a three-point system is a much better idea than the former on its own.