The schism between schools of thought on the value of analytics in hockey has played battleground to a great many heated arguments. On one side, we have an army equipped with spreadsheet data to support its claims, while the old guard leans on tradition, the eye test, and a counterargument built upon a “WATCH THE GAMES!” refrain.

We’d like to bridge the gap between the parties that love this game. In an effort to reach this goal, we’ve quantified something that’s been the subject of very little analytical research: Hockey fights. So drop your gloves, grab a calculator, and settle in for a lesson on punch Corsi.

When the gloves come off, everything else comes to a halt.

A fight’s impact on the scoreboard is generally limited to a matching pair of five-minute penalties. Wins and losses are left to the eye of the beholder.

There is no panel of judges keeping score. This is not Blades of Steel where the winner walks away while the loser sits in the penalty box for two minutes. Participants split and make their way to the penalty box or dressing room for repairs.

Humans seek explanations for things they’ve witnessed. We use knockdowns, knockouts, and blood spilled as a measure of who won a fight. Cast your vote at hockeyfights.com and count ‘em up. The trouble with simply relying on a voting process is that bias is inevitable. This is where analytics come into play.

We’ve moved past the revolution phase of hockey’s relationship to analytics. Most teams employ a team of analytics experts to assist in many of the day-to-day operations of an organization. Counting goals and shots hardly tells us the complete story, thus we lean on shot attempts (Corsi), differentials, and a host of other percentages that help paint a complete picture.

When it comes to fisticuffs, punch Corsi tells us more about a fight than a simple slip-up or knockdown can. It’s about answering ‘who controls the fight?’

Punch Corsi is calculated as follows:

Punch Corsi number = (punches on target for + missed punches for + blocked punches against) – (punches on target against + missed punches against + blocked punches for)

According to a 2013 study by *Dr. Scott Lewis, punch Corsi data collected from January 19-March 20 during the lockout-shortened 2012-13 season indicated Mike Brown led players with a minimum of six fights with a punch Corsi number of plus-48 through eight bouts. By comparison, human punching bag Krys Barch was minus-51 in six tilts.

Authors L. Jon Wertheim and Sam Sommers dedicated a chapter in their book This Is Your Brain on Sports: The Science of Underdogs, the Value of Rivalry, and What We Can Learn from the T-Shirt Cannon to hockey fights. More specifically, Wertheim and Sommers delve into a perceived “home field advantage” in fighting.

Using research conducted by Joe Walsh, a data scientist at the University of Chicago Center for Data Science and Public Policy, the authors noted a dramatic difference in enforcers’ win-loss records at home compared to on the road. Walsh pooled data from 6,000 fights listed on hockeyfights.com (the total with a “statistically meaningful number of votes”) and determined the scrapper from the home side was 20 per cent more likely to earn a “victory.”

Walsh’s data revealed home players won 41 per cent of fights, the visitor won 35 per cent, with the remainder resulting in draws. Hockeyfights.com’s win-loss information for bouts matching Walsh’s criteria indicated Tony Twist, one of the game’s toughest customers in the 1990s, was 7-1-1 at home versus 1-2-4 on the road.

What does punch Corsi say about Twist’s fights?

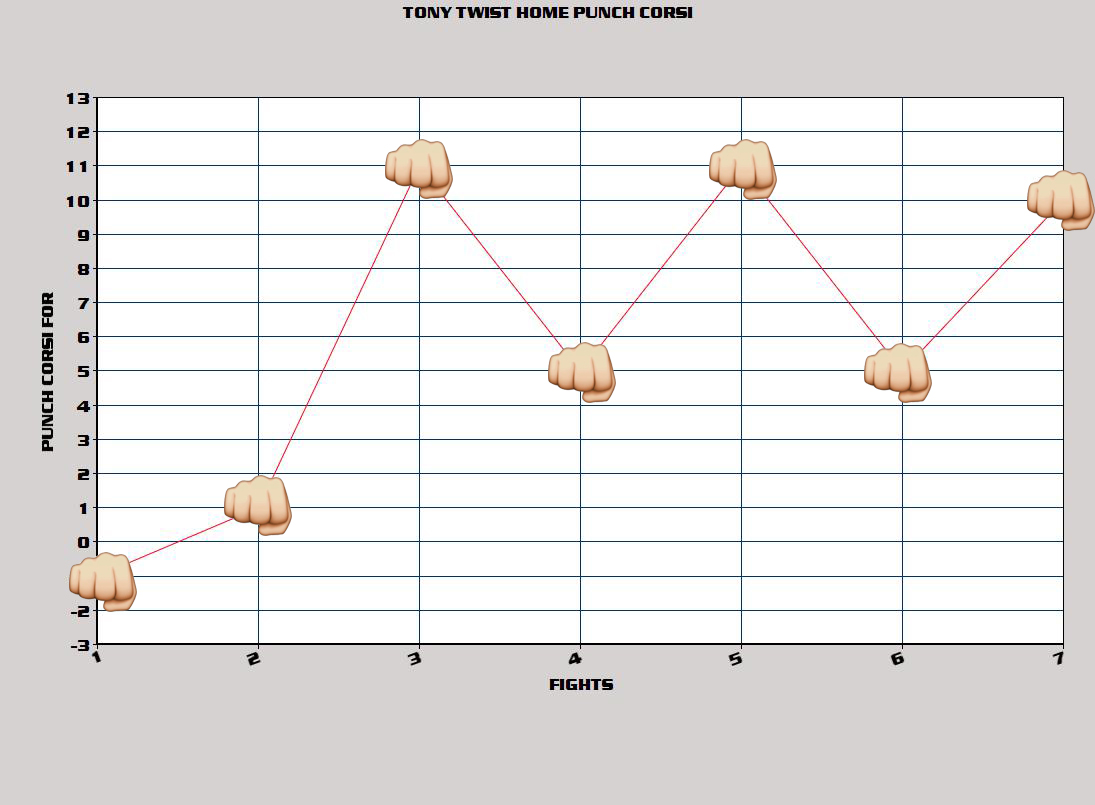

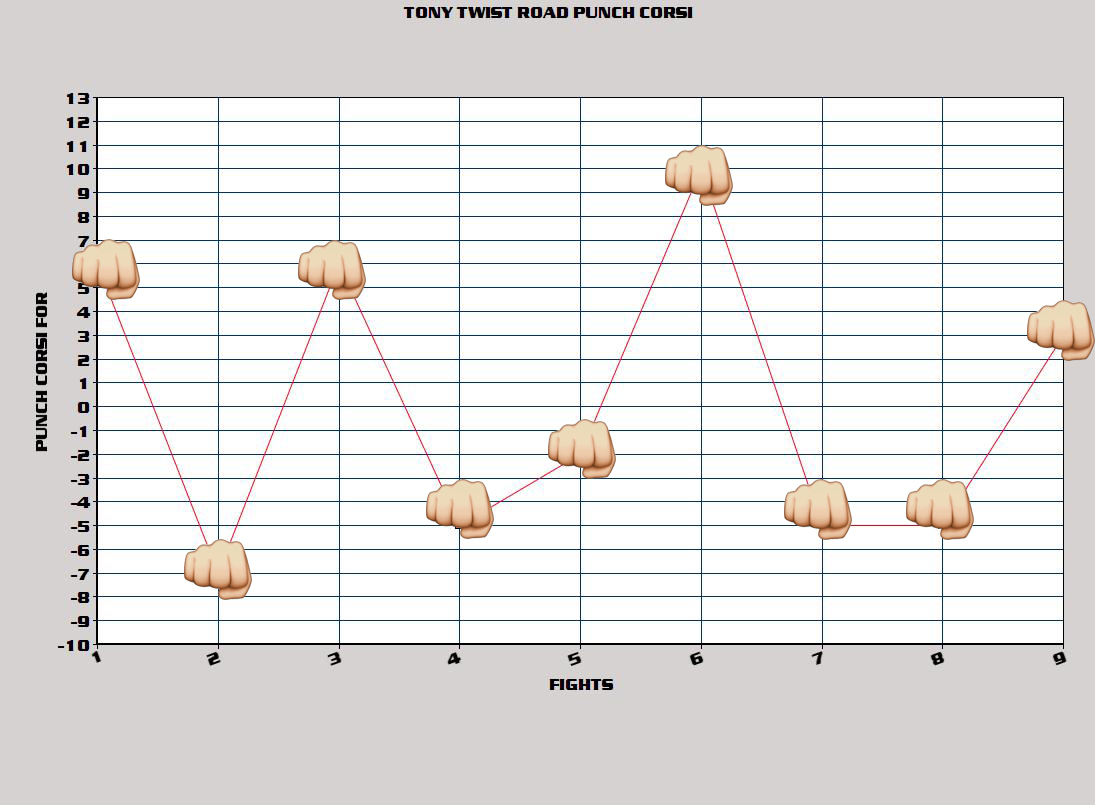

Using a positive score as a win and a negative total as a loss, a count of punch attempts revealed a similar 6-1 record at home compared to 4-5 on the road. Twist’s punch Corsi number in home fights was plus-42. His road total was plus-1. A stark contrast indeed.

Here’s a look at Twist’s performance on home ice in chart form:

Now take a look at the peaks and valleys in his tilts on the road:

Part of the disparity in Twist’s home/road splits can be chalked up to randomness like slipping a stick, punch quality (oh, it’s real), or early intervention from officials. Wertheim and Sommers point to possible changes in brain chemistry. Based on studies conducted on mice, a fight in a familiar environment can lead to spikes in testosterone levels, which may lead to increased aggressiveness and ultimately a better performance on home ice.

Go ahead and ask Tony Twist what he thinks about being compared to mice.

Accessible data from Twist’s fights ostensibly supports the theory that enforcers win more at home, but what does a look at hockeyfights.com’s records compared to punch Corsi numbers reveal about a random 20-fight sample from the 2015-16 season?

From the perspective of the home player, a random sample of 20 fights from the 2015-16 season revealed a record of 7-3-10 using hockeyfights.com’s voting results as a measure. The same sample produced a record of 8-12 for the home team’s combatant using punch Corsi.

Collectively, home players totaled a punch Corsi numbers of minus-35. Lopsided visitor’s wins by Micheal Haley over Derek Dorsett, Nick Ritchie over Jarred Tinordi, and Darnell Nurse over Max McCormick heavily influenced this result.

While it’s too small of a sample to debunk Walsh’s research, it does tell us that the eye test is a rather accurate measure when it comes to hockey fights.

There’s great value in underlying numbers like punch Corsi but, of course, context is king. So watch the fights,nerds.

*Not a real doctor

Big thanks to the indispensable hockeyfights.com, a barbarian’s paradise.