Before a life-altering tragedy, Canadian Ron Turcotte won the Triple Crown aboard Secretariat. Now, 41 years later, he returns to Belmont, hoping to witness history.

He doesn’t remember the final steps of his life much better than the first. Tracks left in the paddock dirt, there for a moment, then lost to time, barely worth noting until days later when they were already hard to recall. Harder still, as the days turned to months and the months to years: 36 of them now and counting.

He knows it was late afternoon at Belmont Park: July 13, 1978. Nine days to his 37th birthday, five since his last big win. Just another day at the track until it became the day everything changed.

He has forgotten how the morning unfolded, can’t recall the hour when he rolled out of bed, pressed his feet to the floor and started for the shower. He doesn’t know whether he had coffee with his wife before he walked out of the house or if the Great Dane barked when he closed the door and made for the track. But he knows it was sunny and it was Thursday and he was wearing green and the dirt was dry and the grounds busy, thousands having come to the ivy-covered grandstands to watch the races, none of them knowing they were about to witness the most traumatic moment in the life of one of the most legendary riders of all time.

It was just minutes to the eighth race of the day when he exited the jockeys’ room and took his last steps to the paddock. Walking alongside a bay mare, waiting for the trumpeter’s call: the one that meant it was time to kick off from the ground, pull himself atop his horse and head for the starting gate.

There was no time or cause for reflection once he was in the saddle. The mare felt good and he felt good, and he knew that if he could keep her straight and in the fast dirt that together they could win, just as they had three times before. When the bells rang and the doors sprang free, she exploded and then they were off, galloping through the back stretch until suddenly he was yelling and she was falling and he was rolling through the dirt while the others raced on.

He knew immediately he was hurt. He could feel it in his sternum, which was broken, and in his vertebrae, which had been crushed to powder. And he could see it in his legs, which were tangled like a rag doll’s. Then he reached for them and when he touched them he began to panic. He was still panicked, his eyes wide and filled with fear when an outrider arrived at his side. “My back is broken,” he said. “I’m paralyzed.”

A percussion of hooves beats against freshly combed dirt as stallions, geldings and mares practise their gallop through the home stretch, passing Ron Turcotte, who has rolled himself to a shaded spot near the finish line. He misses this track. Never tires of its sights or sounds, the ones that remind him of a life he hasn’t lived since the day he lay stricken over there on the back stretch.

Early morning at Belmont Park: June 6, 2014. One day to the Belmont Stakes. Thirty-six years since Turcotte last sat on a horse, just as many since anyone has come to this track and won sport’s most elusive prize. He’s here because he wants to be a part of history again. To look out at the place where his life changed—twice—and to be among the spectators in case a man and a horse once again win the Triple Crown, just as he did, all those years ago. He has hopes that tomorrow this track will be abuzz with excitement and that people will fall back in love with one of the oldest sports around.

He turns his chair from the track and wheels himself toward his 68-year-old sister and her husband, who’ve come with him from their home, 1,000 kilometres away in Grand Falls, N.B. He wants to show them something special before the crowds arrive and this place gets crazy. He rolls through the grandstands, leading them to the paddock—to the very spot where he took his last steps. Then he points to a bronze statue of a colt he once knew. “That’s my horse,” he says.

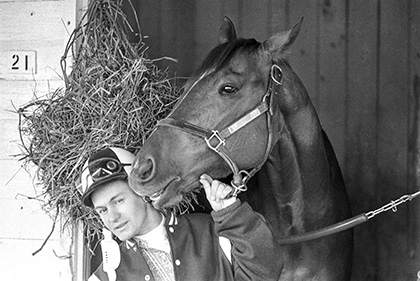

He doesn’t know how many times he’s come here to admire that statue, but he knows this could well be the last. He’s older now than most people thought he’d get, though he masks his 72 years with a young man’s smile while he poses for a photo with his horse.

Back in the grandstands, he nods at passersby who stop to stare and wonder if maybe the little man in the polished cowboy boots and with the diamond-studded rings on his fingers is someone they should remember. He sits by the track, reflecting, but not dwelling, on a life both lived and lost. “That’s where it happened,” he says, pointing at the finish line. “Where I turned my head and they took that famous photo.” It is a photo that millions have seen, and nearly as many remember of a horse—the fastest to ever live—galloping toward history. Taken on June 9, 1973, in the closing seconds of the Belmont Stakes, it captures the great Secretariat approaching the finish line a full 31 lengths in front of his nearest rival while his jockey looks over his shoulder, as if admiring the growing distance between him and the next rider. It remains one of the most iconic photos in all of sport, republished every spring when a horseless society looks to its past to rekindle its love for a sport that fell out of fashion a long time ago. Those who see it recognize the horse immediately. But 41 years later, the rider is harder to identify.

There was a time when Turcotte’s name and face were frequent fixtures in magazines and newspapers across North America, and when men in Hollywood wanted to turn his life into a film. His mythological rise was fairy-tale fodder for the masses. The story of an impoverished boy who raced his father’s workhorses around the barn only to grow up and set the track records at the Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes and Belmont Stakes. A triumphant tale with a tragic twist about a man who was crippled while pushing an underdog horse down the same track over which he once flew. Yes, Ron Turcotte’s life could have made a beautiful movie. But he never cared much for the dramatist’s flair. “The real story,” he says, “is dramatic enough.”

It was a long time ago, 69 years he reckons, but he remembers it was summer and he was playing in the barn behind the family home, climbing through the hayloft, as he often did, when his older brother pulled the ladder away, forcing him to jump down and land square on an old work-mare named Queen. That was the first time he ever sat on a horse.

Growing up in the age of Gene Autry and the Lone Ranger, Turcotte dreamed of one day becoming a cowboy. It didn’t matter that cowboys were already fixtures of the past. Roaming the wilds with reins in his hand and a six-shooter on his hip seemed a realistic-enough dream for the boy who milked all the cows in the barn by the age of eight. He was 10 when he got his first rifle and was soon supplying rabbit, partridge and the odd deer to the family dinner table. The third of 12 children, Turcotte and his siblings weren’t so different from any other 1950s French-Canadian family in rural New Brunswick. Except they happened to be shorter than most and still got around on horseback while everyone else was moving about in cars.

Working in the woods with his father, Turcotte would drop up to 100 trees into the snow per day and watch as a chestnut mare named Bess dragged the logs out of the forest. “Never beat a horse,” his father often said, instilling a value that served him well in the years to come. Dropping out of school at 14, Turcotte announced to his family that he was quitting the eighth grade to become a full-time lumberjack like his dad. Five years later he wanted out of the bush, hitchhiking to Toronto with no prospects and only $50 in his pocket.

It didn’t take long before Turcotte was washing dishes at any restaurant willing to serve him. Living in a rooming house in the heart of Chinatown, he spent his nights combing Toronto’s golf courses with a miner’s lamp on his head and four buckets strapped to his legs. He was searching for worms he could sell to fishermen as bait. Then a passing comment from a man whose name he has long since forgotten changed the course of his life forever. It was May 7, 1960, the first Saturday of the month. Turcotte was exhausted from a night of worm hunting. He woke around 3 p.m. and made his way downstairs, where his landlord was watching the Kentucky Derby. In the race was a local stallion owned by E.P. Taylor, a Toronto tycoon. At some point before the start, the landlord looked Turcotte up and down, noted he was only about five-foot-one and asked: “Have you ever thought about being a jockey?”

“What’s a jockey?” Turcotte asked.

“He’s the little guy in white pants.”

The next day, Turcotte hitchhiked to Woodbine Racetrack and the barns north of Toronto, where he got a job cooling down racehorses after they’d been out for a run. His employer was the same tycoon who’d just put a Canadian horse into the Kentucky Derby and nearly won. Within weeks, Turcotte had worked his way up to groom, cleaning horses and stalls. Then one of the trainers told him if he lost some weight he’d put him in a saddle. “I was about 130 lb.,” Turcotte says. “I wasn’t fat, but I wasn’t jockey weight either.”

For nine months, he broke in yearlings and learned how to pace a colt to victory. He wasn’t the only would-be jockey at Taylor’s Windfields Farm, but there was something about his work ethic that set him apart. “Ronnie really practised,” remembers Lloyd Tawse, who rode alongside Turcotte as an apprentice jockey in those early years. “He’d get on a bail of straw and he’d get on the whip. He was whipping the bail as if it were a horse. He was more focused on what he wanted to do than any of us.” When he wasn’t working on his craft, Turcotte was training, running through the rolling hills north of Toronto dressed in a rubber suit. When he tired of running, he’d jump into a car, crank the heater and sweat. He’d often eat just one meal a day, and sometimes he’d excuse himself to the bathroom and vomit. By the following spring, he was nearing his desired weight—105 lb.—but he was still a month away from his inaugural race when he witnessed his first on-track fatality. It was May 5, 1961, and he was standing near the eighth pole at the Fort Erie Race Track, watching his friend Charlie Boland get thrown headfirst from his ride into the concrete base of a rail post. “I ran down to see if he was OK,” remembers Turcotte. “I knew he wasn’t.” Boland died the next day from a fractured skull.

It was a traumatic sight, but Turcotte soon locked the image in a corner of his brain where his thoughts dared not go. He didn’t pause before getting back in the saddle, returning to Fort Erie several times in search of his first victory, which came on April 9, 1962, the second day of Turcotte’s second season as a jockey. He remembers sitting in the gates atop a horse named Pheasant Lane (after its owner’s driveway), not even registering the fact that he would soon be galloping past the place where his friend had died. The track was slow, wet and dangerous, but the stands were full and Turcotte more eager than his horse, which stumbled out of the gate before galloping for the pack. Pheasant Lane caught up quickly, barrelling forth as mud flew from the front-runners’ hooves, splattering Turcotte in the face as he searched for a small opening between the lead horses. Then he used his whip, tore through a hole and didn’t look back until he crossed the wire. He picked up 180 wins that year, finishing the season as Canada’s No. 1 jockey.

It was Turcotte’s reputation for being calm and confident in the saddle—for “sitting cool,” as they say—that earned him a seat atop E.P. Taylor’s most prized possession. Lazy at first, but then skittish and unruly, Northern Dancer was difficult as a two-year-old. Turcotte got him his first win and a few more before being fired after he lost control of the horse in a big-stakes race at Woodbine. Replaced by a top American jockey before the start of the next season, Turcotte watched as his former mount broke the track record at Churchill Downs in the 1964 Derby. But he didn’t let it get to him. He was 23 years old, and heading south himself to a land of clover, bluegrass, creosote fences and endless opportunity.

Turcotte doesn’t know what it was that set him apart from other jockeys. People sometimes said he had a way of communicating with horses, that he could pick up on their thoughts and sense where they wanted to go before they started going there. Those who raced against him all made the same observations. “Horses ran for Ronnie,” recalls John Rotz, one of the many Hall of Fame jockeys whom Turcotte befriended yet often bested. Turcotte never really bought into talk about him being some sort of horse whisperer. He was just a rider, plain and simple. Maybe physically stronger than others, maybe a bit more aggressive and fearless in the way he’d steer a horse into traffic and try to blast his way through. It was a tactic that got him both a lot of wins and a lot of suspensions (120 days’ worth in his first three years). But he insists it was the horses, not him, that were truly special. “I’ve never seen a jockey carry a horse across the finish line,” he says.

Turcotte surprised no one, not even himself, with the speed with which he broke into the American thoroughbred scene. A mercenary jockey from the moment he crossed the border, he rode for whichever trainer was willing to hire him, starting first in Maryland before moving to New York in a matter of months. It was New York, with its three major tracks—Saratoga, Aqueduct and Belmont—that attracted the best jockeys.

The New York jockey rooms were going through a turnover when Turcotte arrived. The great Eddie Arcaro, the last man to win the Triple Crown, had just retired, as had an entire generation of men who’d made their names racing iconic steeds like War Admiral, Count Turf and Bold Ruler. Filling the void were future Hall of Famers like Bill Hartack (the man who inherited Turcotte’s seat on Northern Dancer) and Willie Shoemaker (who eventually won more races than any jockey before him). Into their midst walked a curly-haired Canadian kid with a crucifix tucked in the mesh inside his helmet and a mission to take over their world. He was picking up wins from the day he arrived, and by the end of his first summer in America he’d found himself a Derby contender in a small colt named Tom Rolfe.

Turcotte’s earlier exploits at Woodbine had captured the attention of everyone back home, but now he was a hero, receiving an eight-foot telegram the day before the 1965 Kentucky Derby, signed by 320 people from his hometown. His seven younger brothers were now all making plans to become jockeys, while his girlfriend, whom he’d met on a school bus about 15 years earlier, was readying to marry him. They were all cheering for him now as he exited the gates on a come-from-behind horse with a timid demeanour and a short burst of speed. Turcotte didn’t win the Derby that day, but he did win the Preakness Stakes two weeks later in Baltimore, where he and little Tom Rolfe took the lead in the final few moments of the race and held it for a neck-and-neck finish. It was the biggest day of his life, trumped, three months later, when he returned home to Grand Falls, put on a black suit and walked into an old church—which his grandfather had built—to marry the tall blond from the farm next door. Her name was Gaetane and she was the only woman he ever loved.

Racing in a time when the papers were filled with stories from the track and when jockeys, boxers and ballplayers were about the biggest icons in all of sports, Turcotte in the late ’60s and early ’70s was as close to a superstar as almost any horseman ever was. Rocket Richard and Ted Williams were more like acquaintances, but Joe Louis and Floyd Patterson were pretty good friends. Winning the Preakness had made Ronnie famous, while the daily purses at Belmont, Saratoga and Aqueduct were making him rich. But he still felt like the little guy from New Brunswick. His closest friends remained the ones he’d made growing up and, though he was famous, he was anything but a party boy. His days would begin before dawn when he’d head to the track to work out horses. By noon he’d be preparing for the races, averaging five a day before supper. Then he’d head home to Gae, his four young daughters and his house on the outskirts of New York City.

He liked being home, wrestling with his Great Dane and teaching his daughters some of the more important things in life, like how to tie a fly to a line or fillet a trout or chop wood like a Turcotte. But there was always a promising young horse in a barn somewhere in need of a rider and he wanted a return to the Derby and another run at the Triple Crown.

Winning racing’s ultimate prize meant first finding and securing a mount atop the fastest, most durable three-year-old thoroughbred in North America. In any given year there were 25,000 to choose from. Finding the right horse was one thing. Riding it to victory in three major-stakes races in three states in five weeks was a feat that was first achieved by a Canadian-owned stallion named Sir Barton in 1919 but hadn’t been repeated since Arcaro rode Citation in 1948, and there were wise men in press boxes saying it would never happen again. That after 250 years of inbreeding horses for speed, they’d become too delicate. But by the summer of 1972, Turcotte was pretty sure he was sitting on a Triple Crown contender.

There’s a story that’s often repeated at farms and tracks across America about a horse with three white feet and a heart twice the size of any other. Foaled in a stable shortly after midnight on a spring night in 1970, they say he stood on all fours within 20 minutes of his birth and that the way he held his head high and stared into people’s eyes let them know he was the horse that God built.

Turcotte had heard rumblings from inside the barns at Virginia’s Meadow Stable about a chestnut two-year-old oozing with confidence, who seemed faster than his older stablemate, Riva Ridge, whom Turcotte had converted from a timid yearling to a champion and rode to victories at the Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes in 1972. This new horse was named Secretariat, but they called him Big Red or the Superhorse, and many believed he was the heir to the throne of Sir Barton. Turcotte was down in Florida, preparing Riva for the Derby when he first laid eyes on the big red colt. “He struck me as a pretty boy. I wasn’t sure how well he could run.” Turcotte soon found out when he took him on the track and felt the power filtering through his 1,200-lb. frame. Though the horse was slow out of the gate, he had explosive strength and an ego that could be spotted every time he chased down another horse, blasted past it and then pranced back into his stable. He was a media darling from the age of two, often photographed alongside his adoring owner, Penny Chenery.

Turcotte wanted to be the one to race Secretariat, but he was still a mercenary contracted to multiple stables. Two days after missing out on the chance to ride Big Red in his maiden race, Turcotte found himself atop a lazy colt named Overproof. Battling for the lead at Aqueduct, Turcotte was working his horse as hard as he could, hitting him with his left and then his right hands until he felt the horse’s neck muscles stiffen and his legs begin to wander. “The horse just died under me,” Turcotte says. Soon the jockey was flying loose from the stirrups, thrown to the ground and trampled. His rib cage bent inward, causing contusions on his heart muscles, lungs and back. He was hurt worse than he’d ever been hurt before, but days later he insisted on putting on his boots and silks before some other jockey swooped in and took his next ride away from him.

On July 31, 1972, free of other obligations, Turcotte first raced the greatest horse that ever lived to an easy victory at Saratoga. Then he followed that up with eight wins in their next 10 outings before entering the gates at the 1973 Derby on the handicappers’ favourite for the second year in a row. Two minutes later he was heading for the winner’s circle. It had been 71 years since any jockey had won the Derby in back-to-back years. But that didn’t matter, because Secretariat had just smashed the track record after breaking last and chasing down every horse in the field, somehow running each new quarter-mile segment faster than the last. Two weeks later it was a similar story at the Preakness. They were two-thirds of the way to the Triple Crown and now horse and rider were on the covers of Newsweek and Sports Illustrated, while Time opted to run with just Secretariat’s face.

Turcotte knew the stakes but he tried to distance himself from the hyperbole, arriving at Belmont Park on the day of the big race at 6 a.m., just as he usually did. He spent the morning working out horses, then went home for an omelette and toast before heading back to the track, which was by then abuzz with 69,000 people. He raced and won on a few horses that afternoon, nothing memorable, just a means to stay at ease. Then he went back to the jockeys’ room, threw on his blue-and-white silks and headed out to the paddock to mount Secretariat. He remembers the excitement after the trumpet blared as he rode for the gates through a mass of men, women and children, all of them shouting things like “Go get ’em, Ronnie!” and “Bring it home, Ron!”

And then they were off, Secretariat sticking to the rail and gathering speed while the others lurched forward. It was a mile and a half from start to finish, the longest race of the Triple Crown, and Turcotte knew just as everyone did that countless horses had exhausted themselves racing for the lead in the first mile only to fade before the end. He had planned to race conservatively, preserve his horse before taking off into the home stretch, but as he made for the first corner he could feel Secretariat preparing to fly. So he let out on the reins and shouted: “OK! Let’s go, boy!”

For half a mile he raced neck and neck beside his only real competitor until he suddenly realized that Secretariat was galloping alone, entering the home stretch at record speed. He remembers hearing the roars of the crowd as he made for the wire and feeling as though he were “whistling through the air.” Then he turned his head and looked at the clock just as a shutter closed—capturing the most famous moment in thoroughbred history. Crossing the finish line, he broke the world record and became the first jockey in 25 years to win the Triple Crown.

It was June 9, 1973, and though he doesn’t remember much about who said what in the moments that followed, he remembers how at least four of the five surviving Triple Crown jockeys were there to greet him when he exited of the winner’s circle. “Welcome to the club,” one of them said. He was the youngest member by 21 years.

He always figured he could ride for as long as the best of them, and the best of them seemed to go until they were old and grey. He never liked to think of all the premature ways his career could end.

It was late afternoon at Belmont Park, July 13, 1978: nine days to his 37th birthday, five days since his last big win and he was lying prone in the dirt listening to a friend who was saying “Keep calm, Ronnie. The ambulance will be here soon.” Moments earlier he’d entered the starting gates for the 20,280th time. Seated atop Flag of Leyte Gulf, readying to do what he’d always done. Ten seconds later, he was screaming at the jockey to his left, who was drifting into his lane. “Jeff! Hey! Hey! Jeff!” Turcotte pulled hard on the reins, trying to avoid a collision, but it was no use. Another second passed and he felt the click of his horse’s heels against those of another and then he was crashing. Flag of Leyte Gulf falling forward into the dirt. Turcotte was sprung from his saddle like a stone fired from a sling. He somersaulted twice as he bounced off the ground, breaking his sternum, dislocating his spinal column and crushing two of his vertebrae.

He didn’t lose consciousness until the doctors put him out. When he awoke, he had two metal rods in his back but still no feeling below his chest. The doctors said they’d do what they could. The following week, on his 37th birthday, meningitis and delirium set in. He has hazy memories of a priest giving him his last rites. Then the doctors wheeled him back into surgery, removed the rods from his back and told him he’d never walk again.

For the next 19 years, Turcotte struggled to sleep for more than four minutes at a time. Four minutes and he’d wake up screaming. The pain was always the same, shooting down his spine into a labyrinth of damaged nerve endings, or tightening in his chest just above the point beyond which everything went numb. The doctors offered to make it all go away by cutting off the nerves completely. But he told them no. Some day, someone might find a cure for his damaged spine, and then where would he be?

There never was much hope, but he held on to what was left. It took six months until he was well enough to leave the hospital, returning home two days before Christmas in a customized Cadillac that he could drive using just his hands. The next day, he went out hunting with one of his brothers and shot a deer from a truck. “He was determined to get back as much of his life as he could,” remembers his eldest daughter, Lynn. Come spring he was back at the track, wheeling himself into the jockeys’ room. He talked about training some horses, but eventually realized he was wearing himself out. By August 1979, the doctors were recommending he get away from the sport for his own health. So he headed north to a 27-hectare farm just a short ride from the place where he and Gae had grown up. There he built an 18-room ranch house, which he soon filled with trophies and memorabilia from his previous life.

Then he bought four horses, one for each of his daughters, and began teaching them how to ride. On rainy days, he’d bring out the projector and watch videos of his old races with his family. Sometimes he’d put on the video of his last race. He wasn’t angry at anyone for the accident, though he did sue the jockey who cut him off and the race stewards who let that sort of reckless riding happen race after race. The lawsuit was eventually dismissed, and Turcotte moved on with his life. He wasn’t the only permanently disabled jockey in the world. There were dozens, and they were all in this together now. Turcotte became their biggest advocate.

Back home he did what he could to preserve his independence. He bought a massive red Ford van, had it customized so he could not only drive it but get in and out without any help. Then he went and got a personalized licence plate—“Big Red”—after the horse he’d ridden into history. One day the phone rang with a call from Hollywood. There was a producer on the line asking for three hours of his time and the rights to his life story. He gave them the time but took back the rights when they showed him a script complete with a dramatic scene with him yelling “Why me?!” to a priest after the accident. He didn’t want anybody’s pity.

After a few more years away from the track, Turcotte returned to Belmont, rolled through the corridors beneath the grandstands, went into the jockeys’ room to say hello to his old friends and found the faces were all different. It didn’t bother him until he went back up the elevator, wandered the grandstands and realized they were mostly empty. His former world was changing.

Sometimes, on special occasions, he’d gather with the other Triple Crown jockeys and talk about the old days. Every few years, there’d be one less memory to explore. He wasn’t the last man to win the Triple Crown—Jean Cruguet did it in 1977 on Seattle Slew, as did Steve Cauthen aboard Affirmed just one month before Turcotte’s accident in 1978—but by 2003 there were only three men left and he was the longest-standing member of the club.

He’s twice as old now as when he fell. He almost died of pneumonia a few winters ago, the doctors advising his family to say their goodbyes. He knows he’s fragile, but he keeps strong by wheeling himself around most places he goes. He still lives with his wife in that ranch house near the bush where he grew up. Still pals around with the men who knew him when he was a young lumberjack racing workhorses around the barn. He remains a cowboy at heart, carrying a pocketknife at all times, though he no longer hunts from his van or fishes from his chair. He finished high school at 48, and now occupies his days overseeing his land and making occasional public appearances. He doesn’t think of himself as a forgotten man, though he knows there are fewer and fewer people who remember the things he once did.

An old man in a wheelchair rolls into the grandstands eliciting awe and disbelief as he makes his way through the crowd toward an autograph table stacked high with relics from a long time ago. It’s June 9, 2014: Belmont Stakes day and a half-dozen TV reporters are standing by Ron Turcotte’s side, looking into their cameras, saying: “We’re here with Secretariat’s jockey,” before asking for his thoughts on today’s big race.

A legion of men, women and children, most of them too young to have ever seen him race, begin lining up to meet one of the greatest jockeys who ever lived. Then comes a frail yet elegant old woman, cutting through the crowd with a walker, moving slowly but determinedly until she reaches the man who rode her colt to glory. She too draws looks of amazement—she’s Penny Chenery, Secretariat’s owner, and few in the crowd knew she was still alive. She touches his hand, tells him how wonderful it is to see him again and to be here once more to remember. She sits down and together they start signing photographs of a young man sitting on a horse, looking back over his shoulder as he crosses into history.

Moments before the trumpet’s last call, Turcotte says good luck to a man half his age who’s trying to become the first Triple Crown jockey in 36 years. He excuses himself from the table and struggles to manoeuvre through the growing crowds. He’s come to witness history, but he can’t see the track. He goes back to the table, stacked with photos from his past, and waits for something special to happen. It doesn’t. He watches the crowd leave, then he rolls outside, past the place where he took his last steps, and heads home.

This story originally appeared in Sportsnet magazine. Subscribe here.