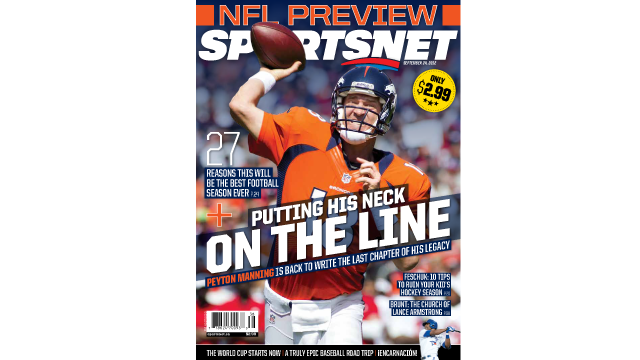

FROM THE AUTHOR: Peyton Manning is a really nice guy. So I felt terrible about wanting him to get hit hard. It’s impossible to write about sports without having a rooting interest—not for the score of the game, but for something critical to the story to happen in front of you. And when you’re writing about whether the man with the surgically repaired neck can take a devastating hit, well, you need somebody to hit him.

When it finally happened, I rooted for Manning to get up, sure, but that was, callously, of lesser importance. Football’s a violent business, after all, and I’m sure Peyton understands.

Here is my story on the recently retired two-time Super Bowl champ from way back in September 2012, when his health was his biggest concern but that second Super Bowl was a dream he couldn’t give up.

PEYTON MANNING’S NECK is straining awkwardly. This is the last sentence anyone in the football world wants to read, but it’s true. It’s 2:30 p.m. mountain time on the third Sunday of the NFL pre-season and Manning’s right shoulder has just been driven into the turf of Sports Authority Field with all the power that 250 lb. of 49ers linebacker Parys Haralson can muster. Haralson is on top of him now, his helmet planted into the right side of his chest, and Manning’s neck is stretched. It looks like he’s trying in vain to pull himself away from Haralson’s helmet.

Everyone else is thinking it. Manning, clearly, is not. He’s said he won’t change a thing, and the unnatural craning of his surgically repaired neck that’s happening right now is proof of that. He’s desperate, not to get away from Haralson’s weight, but to see way down the field, to confirm what the sound of 75,122 fans is telling him—Lance Ball has caught the perfectly placed pass Manning released a split second before Haralson barrelled into him. It’s a 38-yard gain deep down the right sideline and now the Broncos are within striking distance of the end zone. In the seven seconds it took to run the play, plus the two it took for Manning to pop to his feet and start jogging toward the line of scrimmage, a city exhaled, its three biggest football questions answered all at once.

Can Peyton Manning—future Hall of Famer, Super Bowl champion, the NFL’s all-time leader in passing touchdowns and the most accomplished free-agent signing in North American professional sports since Wayne Gretzky went to Broadway—take a hard, full-speed hit, delivered in anger directly to his upper body? Does he still have the arm strength to get the ball downfield with zip on it? Will he still be effective throwing to his right, despite several scouting reports that warned of the toll four surgeries and nerve damage have taken?

Yes, yes and yes. As the question was put to him after Manning went 10 of 12 passing—six of those completions to his right—for 122 yards and two effortless touchdowns to Eric Decker, leading three scoring drives and giving the Broncos a 17–0 lead in less than a full quarter of pre-season action: Peyton, do you think it’s ridiculous for anybody to be questioning if you have any issues throwing in that direction?

Pause. The tiniest of self-satisfied smirks. “Yes.”

The rest goes unsaid in the crowded media room, but Manning’s meaning is clear: Shut up already and let me get to work.

In Denver right now, they smile and they swoon. They are newly in love and nothing bad has happened. Yet. The men all but giggle when you mention his name and the women gush breathlessly about how he chose them over everyone else. They say he looks strong. They talk about the little things they love—his smile, his Louisiana-by-way-of-Indianapolis accent, his work ethic, his wild, gesticulating audibles at the line of scrimmage. Denver is a quarterback’s city. The fans love them and they hate them, but they bond with them regardless.

Along a fence before the game, you can list off the queueing fans by jersey: Elway, Manning, Tebow, Manning, Elway, Manning. Sometimes, a Plummer or—even more scarce—a Cutler sneaks in there. When it comes to quarterbacks, the people of Denver are serial monogomists and Peyton (nobody in Denver actually calls him “Manning”) is more than a crush. They worry about him too much already.

They cared far more that he got up after Haralson’s hit than they did about the two touchdowns and 148.6 QB rating that came after it. But that was good, too. They dream, openly, of the happily-ever-after ending—the “after” refers to at least one Super Bowl, maybe two or three. They buy his jersey and wait by the players’ entrance three-and-a-half hours before kickoff for a pre-season game. And they are too late, even then, because Peyton Manning gets to work early. They drive out to the suburbs and sit on a lush, green hill beside the Broncos’ practice field—thousands of them, day after day, breaking team attendance records to bake in the dry mountain heat of July and August—and they watch him walk through no-pads practices and stretch through exercise drills.

It would seem a waste of time, but every so often he uncorks the kind of throw that was as foreign in these parts last year as non-barbecued meat. They pack more than 40,000 fans into the stadium one afternoon to see him, in an intra-squad scrimmage, run through basic sets against his own defence. They still can’t believe it’s real sometimes, that Peyton Manning is a Denver Bronco. They are so in love that Tim Tebow—the last quarterback to attempt miracles in blue and orange—is last year’s news in a city that is suddenly, and heavily, invested in this year.

But the dirty, nervous secret in this town, which is, for now, the centre of the football universe, is that all this—the Super Bowl predictions, the swoons and grins and the TV cameras and out-of-town writers flying in for practices and scrimmages—could vanish in a puff of smoke. If this is a fairy tale, it is the old-school kind of fairy tale, with blood and guts and danger and no guarantee that anything will work out in the end. The frog became a prince, but the prince’s neck had to be surgically repaired four times and two of his vertebrae bonded together through single-level anterior fusion surgery before it could support the weight of the crown, and nobody yet knows if the wrong painful, awkward jolt won’t topple the whole kingdom. That’s why there’s a split-second pause after Ball’s reception and Haralson’s hit—the cheer starts as an automatic reaction to the play, then catches for a moment in tens of thousands of throats, then returns tenfold as Manning bounces up like a happy puppy ready for a walk. Nothing bad has happened. Yet.

The sentiment behind their fear is real—the Broncos offence is a house of cards built atop Manning’s neck. His chief backup, Caleb Hanie, was booed mercilessly by Bears fans in Chicago during the Broncos’ first pre-season game. They remembered his stint filling in for Jay Cutler last season—four games, three touchdowns and nine interceptions—and they wanted to make sure he remembered, too. Hanie’s backup is rookie Brock Osweiler, a promising prospect but a very raw passer. Fourth-stringer Adam Weber enters his second year yet to attempt a regular-season NFL pass. There is no depth at quarterback and precious little elsewhere on the roster. Denver’s backups were out-scored 40–0 combined after the halftimes of their second and third pre-season games.

Of course, pre-season football is like the acting in a porn film—a strange mixture of going through the motions and trying way too hard to seem into it. But for Hanie, Osweiler and Weber, this stuff is very serious, and thus far they have been failing badly. And, as the saying on the T-shirt goes—a shirt so popular in Denver you can’t find them at the team store anymore—“Peyton Knows.”

And so the legend is teaching his eventual replacements. Sometimes with kindness and patience, sometimes not, but always with an eye toward leaving his new team in some semblance of stability should the all-too-thinkable occur.

“He doesn’t have to coach us like this,” says Osweiler, who keeps a notebook filled with the tidbits he gleans daily from time spent listening to Manning talk about coverages and blitzes and stunts. “It’s not part of his job description.”

Sometimes, Manning just leads by example and dares them to keep up.

“As a younger quarterback, you just have to try to mimic that if you’re given the situation,” says Weber of Manning’s dominant performance against the 49ers. Then he pauses. “It’s not easy.”

But to Manning it is, so he tries to show them how, and it’s become almost a sideline ritual. One of them finishes a drive—good or bad—and jogs to the sidelines. He gets a pat and a quick word from head coach John Fox or quarterbacks coach Adam Gase and then heads over to the professor. Manning always has something to offer, and often he’s got pictures of the defensive coverages and a word or two about how to defeat them. Sometimes it’s just basic tips from a guy who seems to see everything that happens on the field.

“On one play we run,” says Osweiler, “I was shooting my eyes out to the first read a little bit too soon, and he grabbed me right away and made sure, ‘Hey rook, make sure your eyes are on the middle of the field.’ And that’s something that happens on a daily basis. He wants us to get better. And he’s pushing us.”

It’s the kind of thing you do when you’re 36 years old and the man coaching the quarterbacks is two years your junior. You teach, and you make the most of what time you have left.

“You’ve gotta use every single day of practice, every single meeting, in order to get more and more prepared,” Manning says. “I’ll take all the time we can get.”

The scar on the back right of Manning’s neck is not large, nor is it especially ugly, but it still draws the eye. Especially today, when it’s evident just how far Manning has come since his fourth neck surgery 352 days ago. It’s amusing to try to imagine someone, maybe when he’s in his 60s and on vacation in another part of the world, asking Manning where he got that scar. Well, he might begin, I used to play football…

It’s equally amusing, while scrolling down the long list of broadcasters and websites, newspapers and magazines who have sent reporters to watch about one quarter of pre-season football—and the networks who have secured national television rights to six of the Broncos’ first seven regular season games—to imagine a situation in which someone might not know who Peyton Manning is, and what he did for a living.

When it’s all said and done, he’ll have his records, and he’ll have the ring he won with the Colts in 2006, and he’ll have this final chapter, too, the last of his legacy, with every eye in the NFL on him. Again. For a while, though he’ll never admit he thought it, it looked like the book might be closed. Now there are a few blank pages in the back. A few more hits to take and, hopefully, to get up from after a long completion down the sideline. A few more games to win, hopefully when a little more is on the line. A few more lessons to teach. A few more disciples to leave behind so that his impact on the game might last that much longer.

So nobody asks about the scar, because he doesn’t want to talk about it, and it’s kind of irrelevant at this point. Manning is back, the Broncos are, unequivocally, his football team, and he doesn’t need to think about a picture bigger than just that. Even if everybody else will.

This article originally appeared in Sportsnet magazine on September 24, 2012.