GUELPH, Ont. – Colby Rasmus says it shortened his career. Brett Lawrie was happy to escape it. Andre Dawson, the Montreal Expos great who played so many games on aching knees, said simply: “good riddance.”

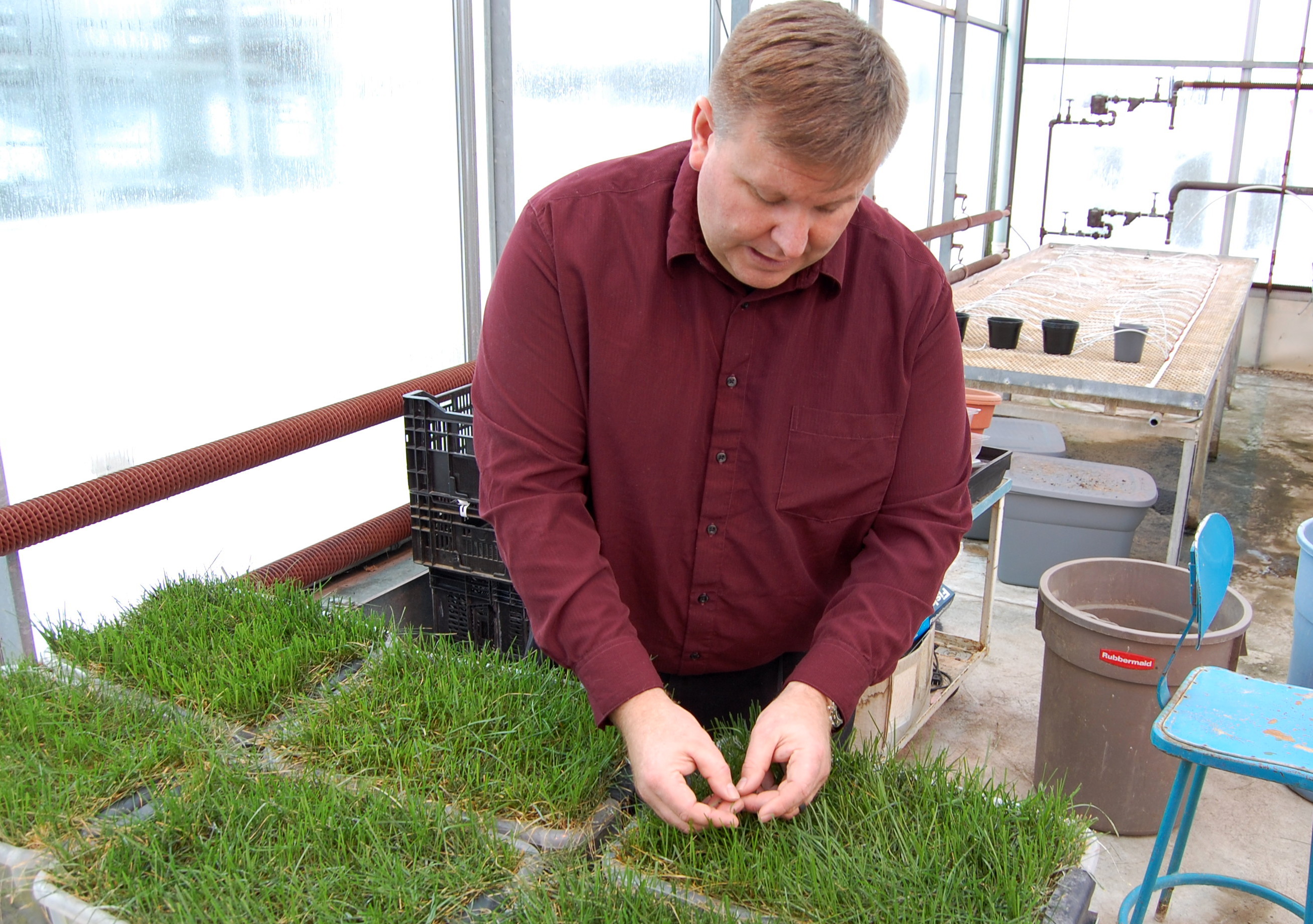

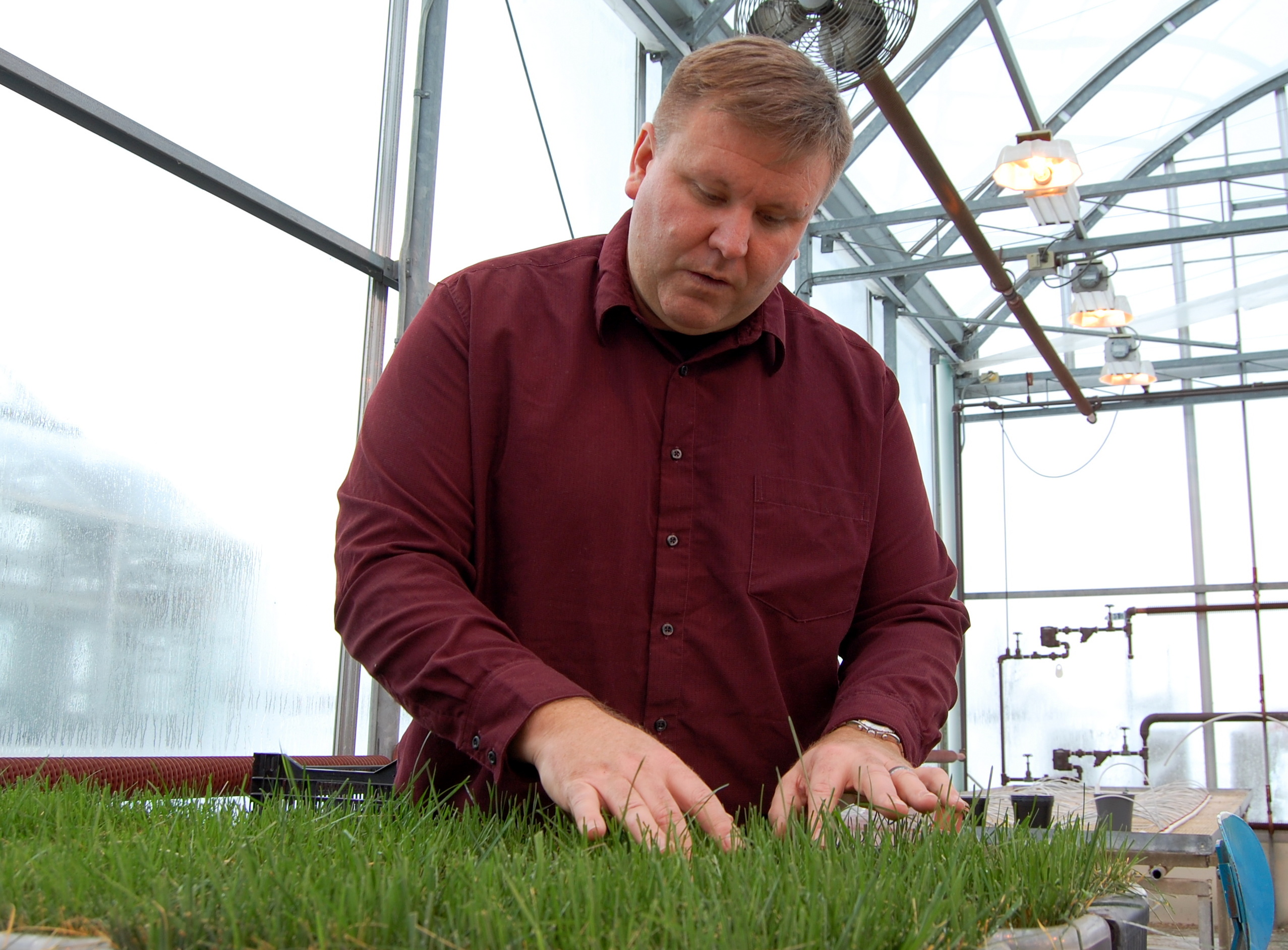

Artificial turf doesn’t have a lot of fans left in Major League Baseball. No wonder University of Guelph plant scientist Eric Lyons feels more than just a little bit of pressure to get this right.

Lyons, one of Canada’s top turfgrass experts, is leading an ambitious experiment by the Toronto Blue Jays to see what it would take to grow real grass inside Rogers Centre in time for the 2018 season. It’s a tall order, and probably one of the most watched sports field transformation projects in North America.

If Lyons and his team are successful, it’ll start here, inside a cluster of laboratories, growing chambers and greenhouses on a campus about an hour outside of Toronto. He’s confident he can pull it off, but admits it’s strange working with the added attention of an entire fan base and the Blue Jays’ brass.

“They really, really want this to happen,” he said. “This is consuming my life. This will be my job for the next year… I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel any pressure.”

Last fall, Lyons quietly planted six plastic bins with a special blend of rye and Kentucky bluegrass during talks with the team, months before the sides announced a deal. He began assembling a specialized group of experts, too.

“I called a lot of colleagues, and asked ‘should I get involved?” he said. “But then I got excited about the science behind it.”

If the sports-loving, ex-football player gets his way, the first large-scale seeding of the Blue Jays’ grass options could begin sometime this fall – right around the time fans hope to be watching a post-season run.

By next year, as that grass grows outdoors on a turf farm, Guelph’s researchers could be running “traffic” tests on samples, designed to simulate the wear and tear of a baseball game.

Spinning aerators with rubber flaps that slap the ground can copy the impact of thousands of hard-hit ground balls and footsteps. Wear simulators can mimic a ballplayer’s twists and turns, and stops and starts, spread over an entire game.

Inside a closely-monitored greenhouse, researchers will block out the sun with black curtains while student athletes doing their best Jose Bautista put on cleats and run sprints, Lyons said.

“We’re not going to use professional athletes. I can’t afford them,” he said. “We have to simulate everything. It’s not good enough to just look beautiful. Your home lawn can look beautiful. But have a right fielder stand in the middle of it, and watch the pounding it takes.”

The scientists will also expose the grass to diseases, play with its moisture content and change the humidity in its soil to learn how the plants respond.

For now, the Blue Jays have signed a year-one, $600,000-feasibility study with the university. If the club likes the findings and determines it’s possible to modify Rogers Centre enough to grow grass, they’ll fund further research.

Lyons says the grass needs to be perfect – not just aesthetically, but it has to perform practically, too.

“When you go to a game, and you see the grass, it just feels like baseball. But if you see artificial turf, it just doesn’t feel quite right. It’s part of the experience,” he said. “It has to look good on TV. But even more importantly, it has to play well.”

When the Blue Jays were still an expansion team, nine major league clubs played on artificial turf. In the 1980s and ‘90s, it was hailed as an innovative playing surface, even a competitive advantage.

Although the look and quality of artificial turf has improved a lot over the years, real grass can’t come soon enough for the Blue Jays. As one of only two teams still using the synthetic surface, it’s cost them leverage with free agents who are worried about the extra toll on their bodies.

Lyons says the biggest challenge will go to the engineers who need to retrofit a stadium that was never designed to grow grass. Among their hurdles will be figuring out how to deal with the extra humidity created by millions of blades of grass, how to give it enough light, how to lower the Roger Centre’s concrete floor and get it to drain properly.

Growing grass indoors is easy enough, Lyons said – they can already do that inside Guelph’s space-age plant labs, where scientists manipulate the light, humidity and water fed to grass sprouts in big, white-walled metal boxes that look like walk-in freezers.

Using these multi-million-dollar growth chambers, they can mimic the exact conditions of the Rogers Centre. Those experiments will help researchers decide which blend of grasses are the best fit for the Blue Jays, and provide data to the engineers who need to build the stadium infrastructure to keep the plants alive.

Lyons is confident it can be done, and done on time, but admits the logistics of retrofitting Rogers Centre in the off-season will be tough. He knows success isn’t certain, and plenty of indoor stadiums have failed at it before.

“Hopefully, we can learn from their mistakes. The Blue Jays want to do this right,” he said.

Last month, he travelled to Houston’s Minute Maid Park, where he met with the head groundskeeper and picked his brain. Lyons will visit other covered Major League parks where real grass is grown as part of his research, too.

Houston knows about the challenges of growing grass indoors. In 1965, the Astrodome became the first major league team to use an artificial surface out of desperation – after attempts at growing natural grass bombed miserably.

Today, the Astros’ grass is fed by giant panes of glass in the west wall of the roof. At Miller Park in Milwaukee and Safeco Field in Seattle, they use special rolling “grow light” systems to help nourish their field. Rogers Centre will likely have to adopt similar tactics, Lyons said.

The science has advanced a lot over the years, and there’s now enough expertise out there to bring real grass back to Canada’s only MLB team, Lyons said. The Blue Jays just need to decide how far they’re willing to go to make it happen by 2018.

“As a scientist, we have an opportunity to answer questions I’ve been asking my entire career. So it’s cool to be a part of this,” he said. “I just hope the Jays give me a ticket to Opening Day.”

Photos by Greg Mercer.