TORONTO – There is intrigue surrounding Chris Colabello as he starts a rehab assignment with the single-A Dunedin Blue Jays on Wednesday, both in terms of what he does now with the bat, and, depending on your outlook, how he ended up in violation of Major League Baseball’s drug program.

The full story on the spate of positive tests for dehydrochlormethyltestosterone – the performance-enhancing substance which earned the Toronto Blue Jays first baseman an 80-game suspension that expires July 23 – and how the anabolic steroid is making the rounds remains unknown. Unlike the BALCO and Biogenesis scandals, no primary point of distribution for DHCMT, also known as Turinabol, has been identified publicly. The group of North American athletes caught with the substance in their system in recent months has yet to be connected to a common point source.

A twist came Friday when one of the players, free agent catcher Cody Stanley, was suspended a second time for the substance. His admission to Ken Rosenthal of Fox Sports that another positive is in the appeals process thickened the plot.

That an athlete already under sanction would continue using a product that got him into trouble defies logic. Stanley, like Colabello and the others, insists he has no idea how DHCMT entered his system, and says he’s searching relentlessly for an answer.

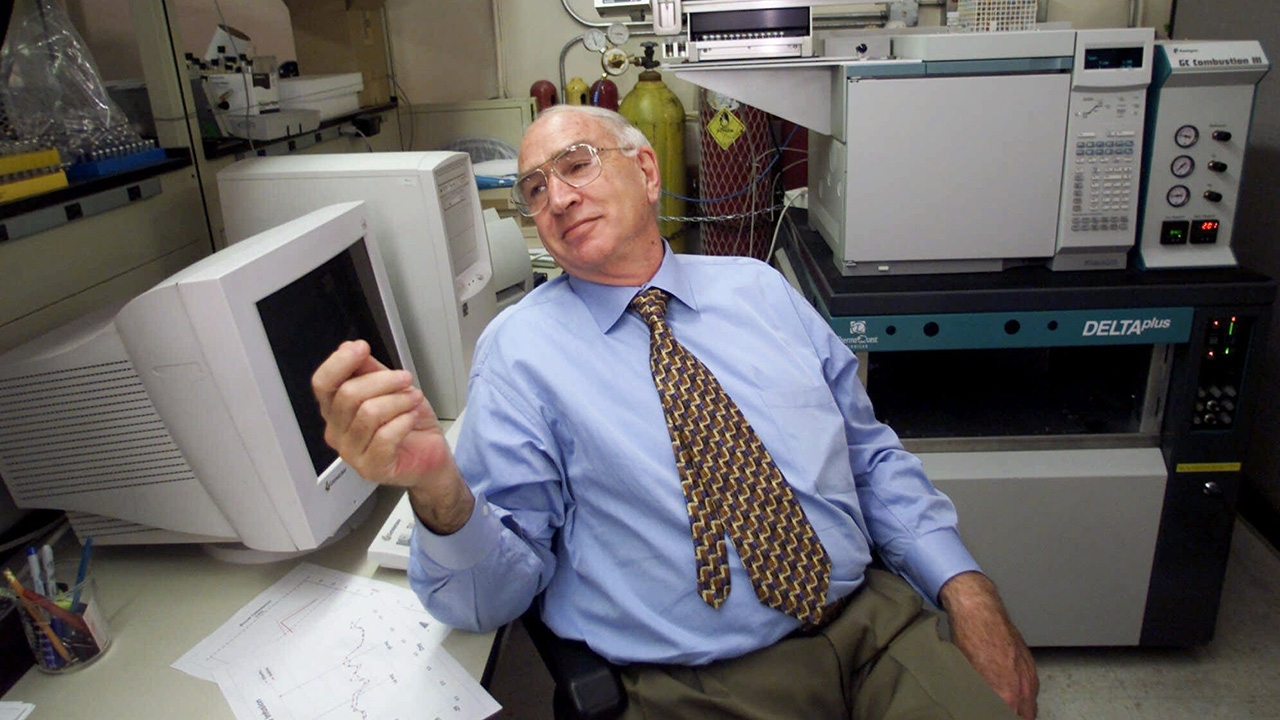

Then there’s this assessment of the testing process from Dr. Don Catlin, the founder and former head of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory, the first anti-doping lab in the United States and one of only three North American sites accredited by the World Anti-Doping Agency.

"The one (DHCMT) case where I looked at the laboratory data, I didn’t think it was very good," he said in an interview with Sportsnet.

Asked what that meant, Catlin, who has overseen drug testing at multiple Olympics and years ago received a grant from Major League Baseball to help develop a test for HGH, replied: "There’s a long process involved and I just didn’t think the laboratory did a very good job in demonstrating that the (DHCMT) metabolite was present in the urine. But I didn’t want to get into it because of a whole bunch of other issues."

While that doesn’t necessarily exonerate the players, from a scientific perspective, isn’t that an issue?

"It’s a huge issue, yes."

Enough of an issue that a player can use it in appeal process?

"Sure."

And present a reasonable case, and perhaps even win?

"Yes. But that would be a huge concern for baseball and (the testing lab in) Montreal."

Because it would call into question the results of other tests and open the door for multiple athletes to contest their doping sanction?

"Right. I did not wish to get into it. But I was interested not so much in the chemistry, but in the source. The three baseball players I talked to were all adamant that they had never used it, didn’t know what it was. And that’s fairly typical, but it also suggests that there’s a source of it somewhere, and my view of it was that it was probably coming from a supplement that they all took."

Dr. Don Catlin, founder and former head of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory, is pictured in 2001. (Damian Dovarganes/AP)

Major League Baseball, quite obviously, has a very different stance on the matter.

"The world’s leading experts on anti-doping science, including the jointly-appointed and WADA-accredited INRS Laboratory in Montreal, have conducted the testing and reviewed the data in all the DHCMT cases and are confident with the scientific methods used to detect and confirm the presence of DHCMT," MLB said in a statement issued to Sportsnet. "Players are responsible for the substances they put into their bodies, and we are aware of dozens of nutritional supplements that are not NSF-certified that may cause a positive test result for DHCMT.

"All players who test positive under the Joint Drug Program are afforded an opportunity to challenge their positive test results through the collectively-bargained grievance process, and present any evidence, including scientific evidence, to a neutral arbitrator who is experienced in drug testing matters. No challenge to a DHCMT positive has been upheld by the arbitrator."

A spokesman for the players union declined comment.

***

The renowned INRS-Institut Armand-Frappier Research Centre anti-doping lab in Montreal, which is also accredited by WADA, does the testing for Major League Baseball’s drug program. Christiane Ayotte, the lab’s director, said science and experience argue against Catlin’s views, but that she didn’t want to jeopardize unresolved doping cases in the system with further comments.

"Suffice to say at this time, that this metabolite is not only used for the detection of dehydrochlormethyltestosterone in our laboratory, but in all other major labs in the world," she wrote in an email to Sportsnet. "It was not identified, discovered by us, but by other researchers who published their work in the scientific peer-reviewed literature. It was included in routine testing by most major labs at the end of 2013. The method was properly validated, as we always do, and this metabolite is very characteristic of this anabolic steroid. In some cases we could also find the parent drug and several other metabolites."

Metabolites are by-products of the way the body processes a material substance, and a correlation can be drawn between certain metabolites and a specific substance. Rather than finding the actual performance-enhancing substance in an athlete’s system, testers often find what’s essentially a signature or a marker of the drug.

There are a few different metabolites linked to DHCMT; Stanley tested positive on multiple occasions for the M4 metabolite, which is called M3 in the peer-reviewed paper by Dr. Tim Sobolevsky referenced by Ayotte that guides testing for the substance.

Christiane Ayotte, director of the INRS-Institut Armand-Frappier Research Centre anti-doping lab. (Graham Hughes/CP)

Colabello also tested positive for the M4 metabolite, and it’s believed the others players caught did as well. One theory floating around to explain the spate of positives is that other metabolites that share similar properties could be masquerading as the M4. Catlin said there are too many variables to say for certain if it’s significant that all the tests identified the same metabolite.

"If they have identified the M4 fully and properly, we believe that comes from a banned drug," he added. "If somebody needs to call it into question, then get another lab to analyze the same samples."

Is there any reason to doubt that DHCMT was in the players’ system?

"It’s a situation that should be confirmed by another lab."

What should the players do?

"Have all their supplements tested. … But it’s better to try to get a portion of the urine that went to Montreal, get somebody like at Salt Lake City to test it."

At the same time, Catlin adds this: "There’s a source (of DHCMT) out there somewhere, you can be sure of that. This stuff just doesn’t appear … the whole story smells very much like a point source that should be found."

***

A decade ago, the detection window for DHCMT was only 2-3 three days before the substance would be out of an athlete’s system. But the discovery of long-term metabolites and improvements to the sensitivity of detection instruments — some are up to 100 times more sensitive than those in the past — expanded that window up to 40-50 days.

As a result, the number of DHCMT positives in sports worldwide has spiked from a few dozen annually to a couple hundred in recent years.

The pivotal research on that front came via the Sobolevsky paper that identified the longest-lasting metabolite he labelled M3 (different labs may give it a different identifier). Any peer-reviewed paper must survive the scrutiny of experts that can be both friend and foe before it sees the light of day as a way to ensure the integrity of the science.

One factor that helps identify DHCMT is that it is a chlorinated substance. Chloride is synthetic and can’t be produced naturally. Its structure is steroidal. That’s why the science believes DHCMT metabolites are unique and can’t come from any other source.

***

Suspended players are allowed to begin a rehab assignment 10 days prior to the end of their punishment, and Colabello has anxiously waited for Wednesday to arrive. The expectation is that he’ll play five games with Dunedin and then five more at triple-A Buffalo leading into July 23, when he’s eligible to return. At that point the Blue Jays will need to make a call on him, and barring an injury that opens up a roster spot, the fact that he has options remaining works against him.

Chris Colabello pictured in April with the Blue Jays. (Fred Thornhill/CP)

That’s the bigger picture. At least he gets to play ball again, unlike Cody Stanley, whose career is in jeopardy.

"While the last three months of my life have been as difficult an obstacle that has ever been put in front of me, I want nothing more than to move past it," Colabello told Sportsnet in a brief interview. "I can only imagine what Cody has gone through and is going through today. Selfishly, I would love nothing more than for this to be resolved so that I can rest assured that it won’t happen again, but ultimately I just want to have an answer for the best interest of baseball and everyone that will ever set foot on a major-league field well beyond the time my career has ended."

During his suspension Colabello says he has searched through "everything – food sources, home products, my dog’s medications, my mother’s cancer medications, and even looked into the science." So far, the answer he’s seeking remains elusive.

Stanley, meanwhile, is hoping Catlin’s viewpoint provides some validation for his defence.

"Dr. Catlin is a world class expert in the field," he told Sportsnet. "I’m not shocked at his response and it certainly holds true to everything I have been saying. Since the beginning of last season I have used NSF Certified, and only NSF Certified products, and I certainly don’t believe the cause of this to be any of those products. Every product I sent to be tested for banned substances has come back negative. I knew that would be the case because all the supplements I was using were NSF approved."

Claims of innocence, of course, are no surprise as the approach comes right out of the athletes-caught-doping playbook. Yet Stanley’s multiple positives for DHCMT suggests something unusual may be going on here.

Daniel Stumpf pictured earlier this season with the Philadelphia Phillies. (Gary Landers/AP)

Boog Powell, Daniel Stumpf, Alec Asher, Kameron Loe and UFC fighter Frank Mir have also tested positive for DHCMT in recent months. All of them save for Loe, who admitted to buying a supplement lacking a safe for sports certification from NSF International, insist that they don’t know how DHCMT entered their systems.

In a statement released through the players union following the announcement of his suspension in June, Powell said: "While I realize this has become a common refrain among athletes faced with such discipline, the truth is I do not know how this substance could possibly have been in my system. … I have already taken proactive steps to look into this situation, and will not rest until there is a full explanation for this result which will vindicate me."

The general public will understandably be skeptical, but these players have actually spent time searching for a culprit. If they’re lying, they’re certainly playing out their stories to the very end.

"You could have a chemist somewhere out there who’s connected to a baseball player who makes the stuff. He’s got to make money, which is usually the bottom line," said Catlin, spit-balling some possibilities on where the DHCMT may have come from. "I suspect that it may have been added to a supplement. A couple of people get a hold of it, and they start to do well and they start bragging about it, and it gets around – that’s usually what happens."

Perhaps the explanation for this DHCMT outbreak is as simple as that. Or maybe there’s more at play. For now, some intriguing questions linger, ones that may or may not change the narrative.