In the five-part series, “What to Expect When You’re Expanding,” executives who helmed year one NHL expansion franchises in Atlanta, Anaheim, Nashville, Minnesota and Columbus share their stories from those early seasons—in part to show Vegas Golden Knights GM George McPhee just how good he and his team have it.

In their expansion start-up, the Atlanta Flames were the shoestring operation that all other shoestring operations should be measured against.

“Once we got going on our scouting, there were four scouts and me out in the field,” says Cliff Fletcher, the Flames’ founding GM. “Back in Atlanta looking after the administrative stuff we had a kid who had never worked in management, David Poile, who was pretty much a year out of college. Both our organization and the Islanders basically had three months to figure out what we were going to do at the expansion draft. It was after New Year’s before we even knew that there was going to be a team in Atlanta. I wasn’t hired until January 4th or 5th. I was a staff of one at that point. We didn’t have a lot of bodies [in the front office] but we had some excellent hockey men. Detroit let us have Donnie Graham, who had been the Wings’ chief scout for years. Other organizations made [some scouts] available to us to help out, but we had a race against time and not a lot of manpower.”

Back in late ’71, the NHL executives wouldn’t publicly admit to being worried about a rival league starting, but behind the scenes they were mobilizing. They were aiming to make life miserable for what would become the World Hockey Association. Their strategy was simple: Tie up the arenas.

“There were two new arenas being completed: the one in Long Island and the Omni in Atlanta,” Fletcher says. “They broke ground for [the Omni] in ’71 and plans were that it would be ready for business in time for the 1972-73 season.”

The Omni was being underwritten by the Atlanta Hawks owner, Tom Cousins, a big player in commercial real estate in the South. The NHL sold him on the idea of a second pro-sports attraction for the arena. The price tag, $6 million, wasn’t about to make Cousins scramble for financing. He poured that sort of money into sprucing up his favourite golf courses, hundreds of millions more into his charitable foundation.

“We had the resources to go out and get to games, but we had a skeleton staff,” Fletcher says. “And it wasn’t just projecting who was going to be protected [by the established NHL clubs]. We had to factor in which players might jump to the WHA.”

Not that the NHL did Fletcher and the Flames any favours in giving them direction on player availability.

“The first thing when I was hired as GM, I asked league officials: ‘The perpetual option that’s in all NHL contracts … is that [reserve clause] going to hold up if it’s challenged in court?’ They assured me that it’s going to be there forever. It lasted about five minutes when the WHA challenged it and the court blew it up. All players on expiring contracts were going to be free agents and so we and Bill Torrey with the Islanders, we were all going to be competing for players who might go to the WHA.”

As other expansion GMs would discover over the years, value could be found in the pool of available goaltenders.

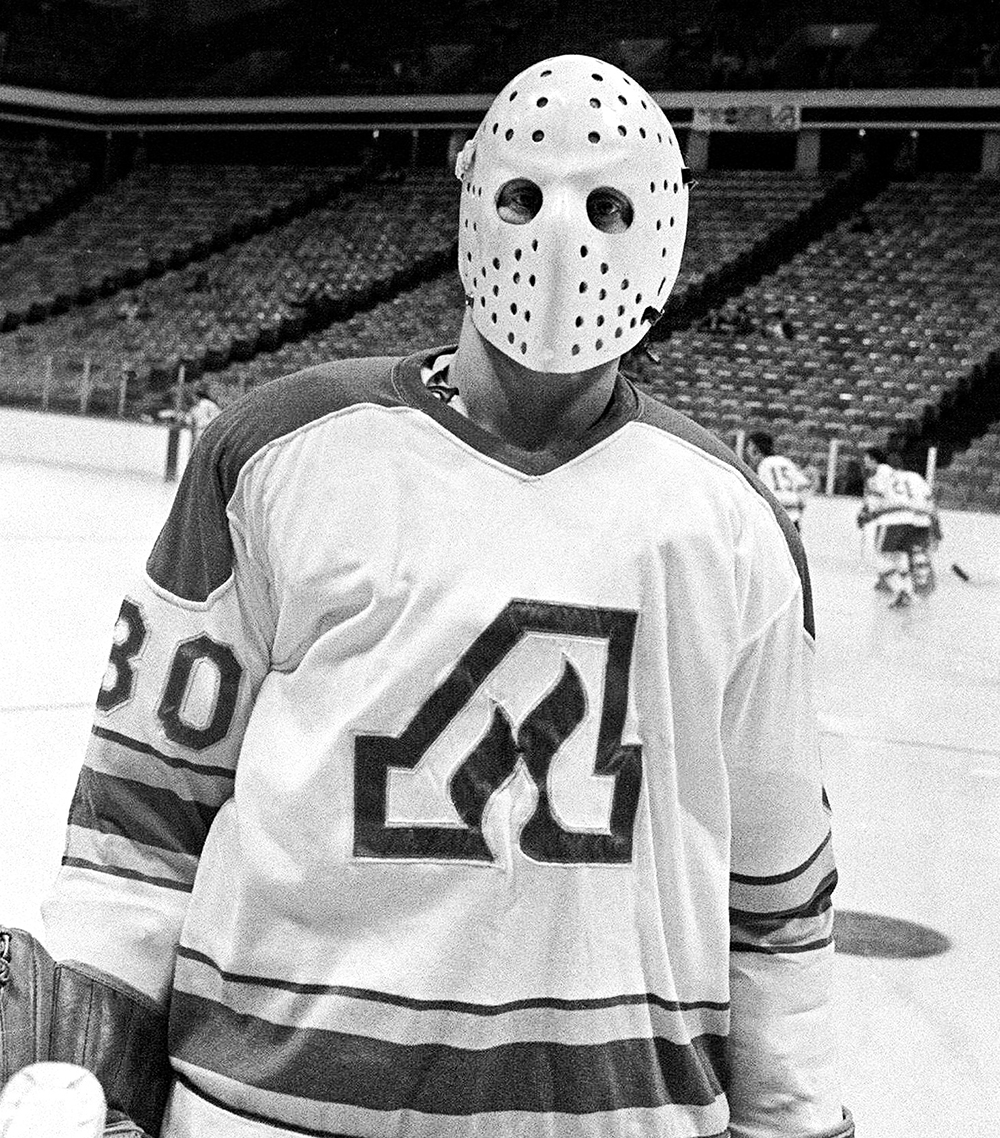

“We did some horse-trading with established teams,” Fletcher says. “We managed to get a real good goaltender out of Montreal in Phil Myre. I worked with St Louis back before the ’67 expansion draft and [back then] we wound up with Glenn Hall, a Hall of Famer, as a goalie. Later on we got Jacques Plante, the greatest of his time. You have goaltenders like that—and someone good is always out there—and you’re going to stay competitive a lot of nights and win a few games when you were outplayed. That’s what we had with Phil and Dan Bouchard—our goalies were out in front of the rest of our lineup.”

By contrast, anything resembling skill among defencemen and forwards was in short supply. Fletcher has a favourite stat that he likes to cite to put it in perspective: “The total number of NHL career goals scored by players we drafted in the expansion draft was less than 70.”

When you look at the names of the journeymen on that original draft list, it’s easy to see what a bad hand the league dealt Fletcher. On the blue line, career minor leaguers: Kerry Ketter (from the roster of the Nova Scotia Voyageurs); Randy Manery (of the Fort Worth Wings) and Larry Hale (who had spent the season with the Richmond Robins).

Up front, only two players had scored more than 20 points in the NHL the previous year: Bob Leiter in Pittsburgh and Ernie Hicke with California. Only one other, Bill MacMillan with the Leafs, had scored more than 10.

When Fletcher worked under Lynn Patrick in St Louis, the Blues and their fellow freshly minted franchises could hope that somehow a talented young player had slipped the notice of one of the established clubs and wound up in the draft pool. Fletcher brought no such illusions to Atlanta.

“I think we all hope to find that talented kid, but back in ’67 and the years that followed it, we realized that it wasn’t like searching for a needle in a haystack,” he says. “It was a haystack but there was no needle and nothing like it.”

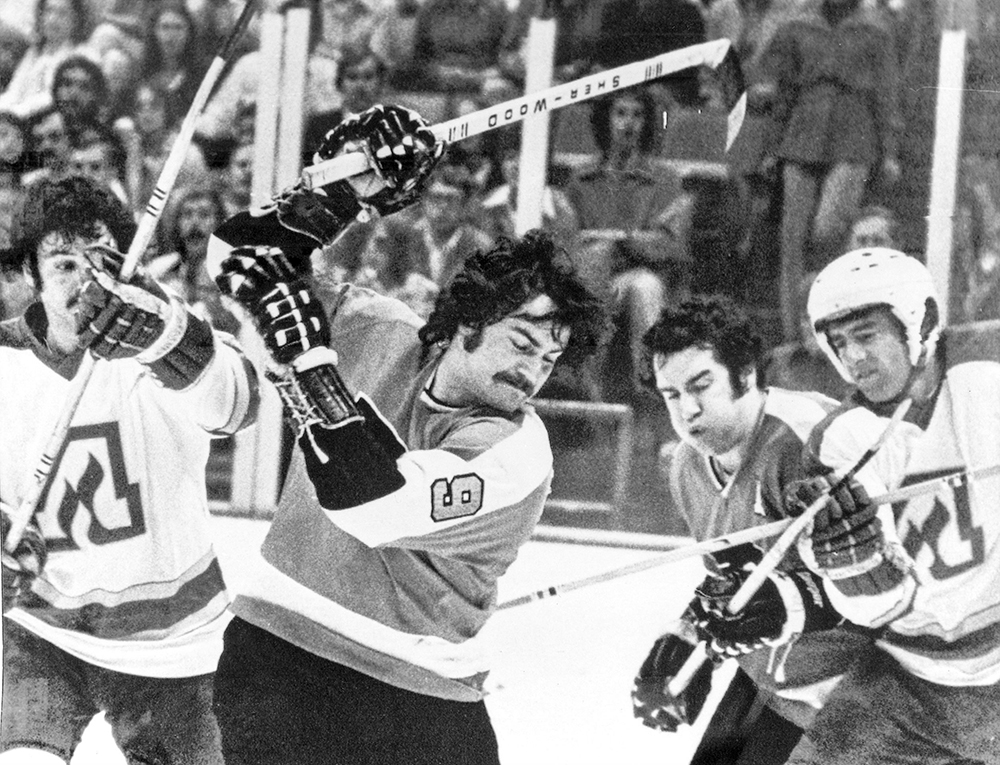

In lieu of skill and flash, Fletcher went out and drafted work ethic and character.

“We got hard-working veterans like Pat Quinn, Noel Price, Leon Rochefort—but as far as young players went there was very little available.”

That was industry opinion at the time. “I remember [Minnesota GM] Wren Blair coming up to me after the expansion draft and saying, ‘Cliff, I thought you did a real good job today,’” Fletcher remembers. “And then he said, ‘Yeah, Cliff, once you get rid of all those guys you should be in real good shape.’”

It wasn’t intended as a dig. And it actually cut to a key strategy in Fletcher’s selections: Having on hand a few depth players who might be of value late in the season to clubs trying to get into the playoffs. In return he could look for young players undervalued by their organizations. The key move that season was a trade that sent 30-year-old veteran Ron Harris to the Rangers for a 24-year-old who had just one assist in 16 games, Curt Bennett.

The Flames stayed in the race for a playoff spot into February of their inaugural season—that’s either a testament to Fletcher’s managerial acumen or an indictment of a top-heavy league depleted by defections to the WHA.

Fletcher’s dealing ran through to the draft. “I made a deal with Montreal so that we moved up from the fifth pick to second, and we wound up with the second, the 16th and the 21st pick in the draft. We took Vic Mercedi with the 16th pick and he only played a couple of games for us, but with the [second-overall] pick we got Tom Lysiak and the 21st we got Eric Vail, and we were on our way.”

In their second season, the Flames made the playoffs, losing in the first round to the Philadelphia Flyers who went on to win their first Stanley Cup. More importantly, though, Fletcher had established a game plan.

In the 1973-74 season, Lysiak finished as the runner-up to the first-overall pick in the draft, Denis Potvin, for the Calder. The next season Vail won the trophy. Bennett wound up being the cornerstone of the franchise in those early days, becoming the first American-bred player to score 30 goals in an NHL season.

The Flames lasted only eight seasons in Atlanta but made the playoffs the last five, albeit only winning two post-season games in that stretch. Other than the trade for Bennett and the acquisition of Lysiak and Vail in the entry draft, the best move Fletcher made was the hiring of Bernie Geoffrion as coach. In the first three seasons in Atlanta, the colourful Geoffrion—more than any player—was the face of the franchise, a cigar-smoking, jovial character and quote machine, who after his coaching days wound up in Miller Lite commercials and made Atlanta his adopted home.

Things didn’t last in Atlanta, but Fletcher did get his Stanley Cup as a GM in Calgary. He landed in Toronto and was the Leafs’ GM for their near-glory stretch in the early ‘90s. After stints in Tampa Bay and Phoenix, Fletcher returned to the Leafs as an interim GM in 2008 and remains with the club, at 81, serving as a senior advisor who lives up to his job description.

Fletcher wouldn’t care to go back to a start-up at this stage of his life, but he admits that he envies George McPhee’s position with his Vegas Golden Knights.

“George has the full year compared to the time we had, and he has put together a great staff,” Fletcher says. “Still, the key things are the fact that there’s fewer players teams can protect [and that] Vegas is coming in alone. He has an opportunity to make all kinds of deals with clubs. It was a lot harder for us in Atlanta because we didn’t know what the Islanders were going to do and signability [with the WHA] was going to be an issue. It wasn’t like the draft with St. Louis in ’67—yeah, with five other teams there’s just no control over things, but at least if you drafted someone you knew he was coming.”