He sat in the same spot every night, puffing his cigar in the February chill.

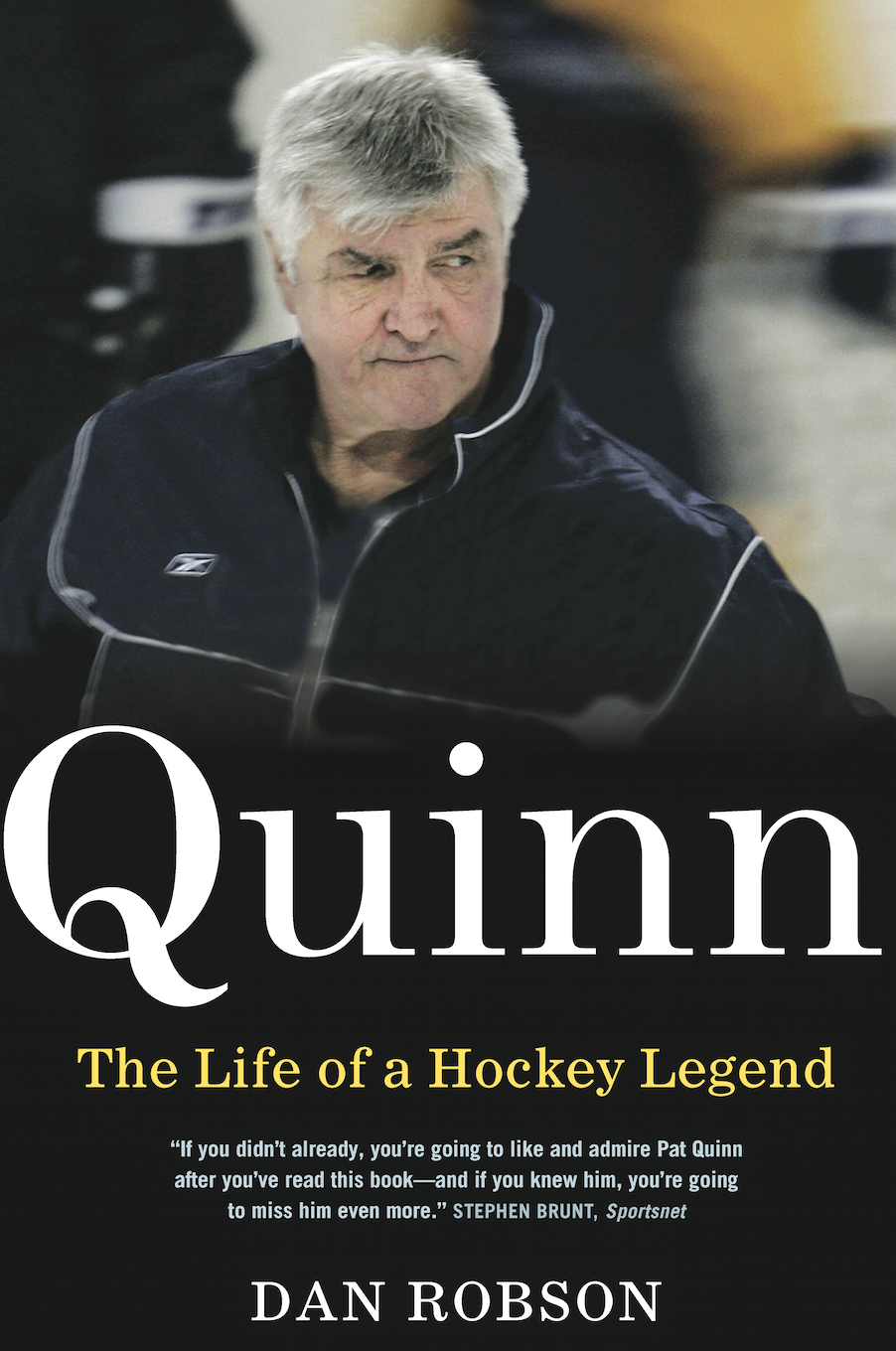

A year from 60, hair full white, Pat Quinn faced the most daunting task he’d experienced in a quarter-century of coaching. It had been 50 years since Canada had won the Olympic gold medal in the sport the nation claimed as its own.

Quinn had been just a kid skating at Mahoney [the park next to his boyhood home] when the Edmonton Mercurys brought home gold from the 1952 Olympics in Oslo, Norway. He had barely noticed it then, when the tournament was played by amateurs. But every day leading to Salt Lake, Quinn was reminded of the great gap between the last gold and now.

Canada’s claim to hockey supremacy had been severely damaged by the 1998 Olympics in Nagano, where the nation’s best finished fourth. Salt Lake was about righting that wrong. Nothing but gold would atone for what wasn’t won four years before.

Every night, Quinn sat on that bench in front of the Canadian Olympic team quarters, puffing clouds of smoke into the dark sky as the nation’s finest athletes stopped to confide in him their fears and anxieties. His evening chats with the athletes who passed by became so common that volunteers put a “Pat’s bench” sign over the spot where Quinn always sat. He’d ask them questions about their lives and share stories of his own. Mostly, though, he’d listen.

Quinn had great respect for the young athletes representing their country, who battled to achieve their dreams with little financial reward, if any. The “Big Irishman” was a figurehead for the entire country at the Olympics. Heroes like Wayne Gretzky were certainly an inspiration, but Quinn was something different—he was a force of stability and confidence. He reflected a Canadian ideal: not necessarily the most talented, but nevertheless unrelenting in the pursuit of greatness.

While he could be hard on his own players, Quinn didn’t have the expert knowledge of the sports the other athletes played. And so he just listened and learned, offering some of the philosophical and physiological advice he’d gathered through a lifetime in sport. He sat with snowboarder Jasey-Jay Anderson, who knew nothing about hockey and didn’t follow the NHL.

When freestyle skier Steve Omischl sat next to him, they spoke for more than an hour. The 23-year-old had just crashed in the first round of his event and placed 11th. He was devastated. While his own coaches only wanted to talk about what had gone wrong, Quinn told him that all the hype and stress were just distractions. He told Omischl not to worry about the media, not to worry about his coaches—not to worry about the expectations that come with a nation expecting success.

“Don’t worry about what other people think,” Quinn told him. “Just do what you need to do to get the job done.”

The sparkles on Quinn’s socks were evidence that he’d taken his own advice. Quinn had been chosen by the greatest hockey player in the game’s history to lead a team stacked with some of the best players of a generation — Mario Lemieux, Joe Sakic, Rob Blake, Martin Brodeur — into a tournament where a single game could forever put an asterisk of failure next to your legacy in the game.

If Team Canada failed to win gold — even if it won something less, even silver — the disastrous outcome would be pinned on Quinn. “How could Quinn lose with a lineup like this?” the radio hosts and columnists would bray. Others would certainly feel the wrath, but as head coach, every move Quinn made would be dragged out and judged, endlessly. Quinn was the captain of this ship. He knew it. But he wasn’t bothered by it.

Quinn was used to the outsized overreactions of both Toronto and Vancouver, among fans and in the press. And he knew this was an incalculable exponential of that. Despite that, sparkles fell from Quinn’s slacks as he walked. They were affixed to his lucky socks and briefs — a gift from his grandkids, decorated with love and glitter glue.

Along with his six-year-old grandson, Quinn, he now had two granddaughters — four-year-old Kate and Kylie, who was just six months old. While some knew about the lucky socks Quinn wore for every game he coached at the Olympics, only a few would learn of the shimmering tighty-whities beneath his suit.

Canada was moments away from a gold medal.

In the stands, Sandra Quinn watched as the final seconds ticked away toward the end, just as she had almost 40 years before when her newlywed 20-year-old husband was about to win the Memorial Cup. The Canadian fans in the crowd bellowed out celebratory renditions of “O Canada.”

Before the game, Quinn had turned to Keith Hammond, who sat behind the bench for security, and asked him to make sure he could bring Sandra, Kalli and Valerie down to the ice if the team won. When Canada’s victory was clear, Hammond ran up to the concourse to find them waiting at a security checkpoint, unable to pass. Hammond pulled them through security and raced with them down to the ice to watch the final seconds tick away.

As the players piled onto the ice, Sandra and her daughters climbed onto the bench and embraced Pat. They stayed on the bench while the gold medals were presented and the national anthem played.

Back in Burlington, Ont., the friends and family gathered at Barry Quinn’s [Quinn’s brother] place started a celebration of their own. They were cheering and clapping and laughing as the announcer called out the last moments of the game. In the revelry, Jack Quinn [Quinn’s father] got out of his chair and walked over to Jean [Quinn’s mother] and hugged her close.

When the players crowded in to take a team photo with their gold medals, Quinn shuffled over to the bench and grabbed Kalli to be part of the picture. (He always told her to make sure she was in the centre of photos, so she couldn’t be cut off the ends.) When the flashes went, Kalli was right there in the middle next to her dad, with his puff of white hair, bright-red cheeks and an enormous smile.

A few minutes later, as Jack and Jean gathered their things, put on their winter coats over their Canada sweaters and made for their green van, the phone rang in Barry’s kitchen. “Is mom there?” It was Pat.

The cordless was rushed outside to Jean, just as she was about to climb into the front seat. He’d called. Of course he had. Patrick always did. Jean took the phone and spoke to her boy. The words were brief, but full and complete — and proud Jean Quinn started to cry.

No reporters were allowed in the locker room. The players and the team staff were free to celebrate on their own. But the room was very quiet. Most of the players for Team Canada just sat in their stalls staring at their gold medals, shaking their heads at what they’d just accomplished. The best hockey players in Canada, the best in the world, seemed astonished by the feeling.

Pat Quinn sat in the corner, with that huge smile still stretched between his round cheeks. Wayne Gretzky and Bob Nicholson sat down beside him. After all the pressure, all the planning, all the concerns and doubt — the players had done it.

“It felt like it was the first time I won the Stanley Cup,” says Gretzky. “It was almost surreal.”

The three sat there and cracked open a few beers. Quinn thanked Gretzky for giving him the chance to be Canada’s coach.

Then they just sat there, drinking it in, and didn’t say much at all—as Quinn’s socks twinkled beneath them.

Excerpted from Quinn: The Life of a Hockey Legend,

by Dan Robson. Copyright © 2015 Dan Robson. Published by

Viking Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.