“You learn how to lose quicker than you lose how to win.”

—Charlie Simmer, California Golden Seals

Producing E! True Hollywood Stories and TV specials like Lindsay Lohan: The Road to Jail and Did Elvis Really Die? pays the bills. But Mark Greczmiel, a documentary filmmaker with hockey in his heart, wanted to create something that held a little more importance.

Hard work, debt and love have birthed Greczmiel’s wonderfully quirky time capsule, The California Golden Seals Story, which is now available on iTunes.

Born in Vancouver, Greczmiel’s family moved to California when he was seven. Two years later, the 1967 NHL expansion brought him inspiration and entertainment in the form of the Golden Seals.

Growing up just 10 minutes from Oakland Coliseum, Greczmiel’s dad — to whom the doc is dedicated — would bring Mark and his two brothers to Seals games. Tickets were just $6 a pop, and the stories were funny, sad and priceless.

“I remember my very first game was against Toronto, and my brother caught a puck in the stands,” Greczmiel told Sportsnet last week via phone. “I grew up idolizing these guys.”

[relatedlinks]

A budding film nut, Greczmiel would tote his Super-8 movie camera to the rink and shoot highlights at the games. When he moved to Edmonton for a news gig after graduating university, he produced a couple pieces about the Seals’ hilarious and tragic history.

After reading Brad Kurtzberg’s Shorthanded: The Untold Story of the Seals, Greczmiel was inspired to pour his passion for the forgotten franchise into a two-and-a-half-year labour of love, running two crowdfunding campaigns and carving out time to work on his Seals documentary.

“It was a leap of faith. It was just me and my camera. I didn’t have a crew. And I traveled all the way across Canada and the U.S. with my video camera and some lighting and sound gear,” says Greczmiel, who conducted more than 30 interviews for film. “I’m still quite a bit in the hole.”

Working on a micro budget, Greczmiel was flooded with photographs from Seals fans who learned of his project and hit the jackpot when he discovered a Bay Area library that had housed local TV news stations’ dusty footage of the hockey team for more than 40 years.

So difficult was it to cram all the innovative, goofy and embarrassing tales of Bay Area’s original hockey club into 90 minutes, Greczmiel has a DVD just as long stuffed with stories you’ll never hear.

From white skates to orange pucks, from Hell’s Angels to a bare-naked lady, we highlight the 17 most interesting bits from a wild nine-year NHL run of the Golden Seals.

The Seals almost became the Canucks

Under financial struggles just two months into the Seals’ inaugural season, the original Barry Van Gerbig ownership group considered relocating the Seals to Vancouver, an eager and more natural hockey market. The idea was shot down by the NHL because it wanted two California-based clubs. Buffalo also expressed interest.

Gretzky’s first NHL game featured the Seals

Wayne Gretzky’s grandma took the young fan to Maple Leaf Gardens that night, and Toronto blew the Seals out of the building.

“When I turned pro in ’78, Gary Smith was the goaltender with the Indianapolis Racers, and I told him: ‘I saw you my first game when I was six years old. You were in net, and you weren’t very good,’ ” Gretzky laughs. “What do I think the Seals’ legacy is? I don’t want to be mean, but not very good.”

Greczmiel was thrilled to land the Great One for the film.

“In Ontario, he was friends with the families of two of the players,” the filmmaker says. “He knew the history. It gave the project a lot of legitimacy.”

Not all NHLers were thrilled to play in paradise

Saskatchewan-born defenceman Bobby Baun, whose lone Seals season was sandwiched between stints with Toronto and Detroit, hung a winter landscape mural in his room and would stare at it before home games to get in a “hockey mood.”

Eventually, Seals recruits warmed to the idea of hockey life in California. Most spent all their spare time golfing.

White skates, orange pucks

Flamboyant Oakland Athletics owner Charles O. Finley purchased the Seals in 1970, outbidding Roller Derby honcho Jerry Seltzer. Finley had zero interest in or love for hockey but was an outside-the-box thinker who opened the 1970-71 season by trotting out a skating mule.

“Charlie O was a clown, basically,” goalie Gary Smith says in the doc. “A wealthy clown.”

First, Finley added “Golden” to the team nickname (to lure San Franciscans) and gave the Seals kelly-green and gold uniforms (with matching skates!) so their colour scheme would match that of his baseball club. The players all wore green blazers and carried green suitcases, which Greczmiel said he’s seen selling for more than $1,000 on eBay.

The Seals’ shade of skate soon switched to “polar bear white” because the A’s all wore white cleats.

“In Canada, you equate white with figure skates,” Greczmiel says. So, naturally, the Seals became a laughingstock to their opponents.

It gets worse. On the black-and-white TV sets of the time, the players’ white boots gave the appearance they were sliding around the ice on stumps.

And because Finley insisted the skate boots remain pristine, he had the trainers paint and repaint them to cover scuffs between periods. The Seals complained their feet were getting heavier as the season wore on and the layers of paint thickened.

“I remember thinking, ‘Wow, if I play in the NHL, I hope I don’t have to wear white skates,’ ” Gretzky says.

All about the name on the back

Did you know the Golden Seals were the first team to put names on the backs of their sweaters?

Conservative NHL owners balked at the idea for fear the splashy surnames would eat into their coveted program sales, so the Seals would travel with two sets of road jerseys in case one of the visiting team’s owners got too heated over their forward-thinking manoeuvre.

We’re going streaking!

As the Bay Area pro team garnering the weakest interest, attendance was weak and ad budgets were minuscule, as low as $5,000 for an entire season.

“All they could afford was a couple of billboards, so they were trying unique ways to market,” Greczmiel says.

“They hired a streaker—the girlfriend of the stick boy—to come to a game, strip and skate out from behind the bench as the players came onto the ice after one period of play. I was at that game. In the ’70s, college students were streaking across campus, and the team was so desperate to get publicity, they came up with this thing.

“I remember the yelling and screaming when the girl went onto the ice and skated across. Not only was I able to track down a photo of that, but a woman sent me her Super-8 movies she took at games, and she actually captured that on film, so that’s in the documentary.”

Krazy George and other shenanigans

Among Finley’s list of gimmicks was bringing a real live seal onto centre ice (he just had a nap) and hosting Barber Night, where hairstylists got in free with hopes they’d spread the gospel of live hockey (they didn’t).

George Henderson, a high school teacher, brought a class of students to a game and was so electrifying with his antics, he won a job as the team’s official cheerleader on the spot.

“Management came up to me, handed me a season ticket and told me to come back to Seals games any time,” Henderson says. “Yes!”

So Krazy George would bang on his drum rattle his tambourine, rile up the faithful, and razz the opposing players. Legend has it, he was attacked by Boston’s Terry O’Reilly and has the scar to prove it.

Gucci time

Paradoxically, the Seals’ story is filled with incidents of both scrimping money and blowing it fast.

After one big win in Boston, Finley gave each player $100 cash and took them to the Gucci store in New York City. None of them knew what Gucci was.

On one flight from Boston, the players all bought fresh lobsters and let them loose on the plane. As it was a commercial flight, the paying passengers weren’t particularly thrilled.

At a time when all NHL clubs travelled coach, the Seals would often splurge for first-class on long 747 flights.

This was a franchise that drew as few as 2,500 fans a game. Local television contracts were spotty at best. Some years, they might only broadcast five games. And one season the club went not only without a local TV deal but without a radio deal as well.

They wasted prime years from a fabulous goaltender

Greczmiel considers goaltender Gilles Meloche the greatest Seal in franchise history, even though his goals-against average in California was regularly above four.

“When they got him in a trade from Chicago, he started in Boston against the Bruins — the best team in hockey at the time — and he shuts them out 2-0,” the filmmaker says.

“He was the premier player for years. It was surprising that Gretzky, in his interview, said even though the team lost so often, he thought Meloche was the best player in the league for a number of years because he kept them in games.”

“Come see the next Bobby Orr!”

“The Seals traded away their first-round draft choice often in their existence. When they finally used one, they drafted Rick Hampton from Ontario, No. 3 overall,” Greczmiel said.

Embracing a rebuild under new ownership, the Seals slipped into new powered-blue uniforms and propped up 17-year-old draftee Hampton out of Toronto as the world’s next game-changing defenceman.

“They were so desperate to show everyone they were turning things around, they promoted him as the next Bobby Orr. Everything was: ‘He’s just like Orr! He skates like Orr!’ Plus, Alan Eagleson was his agent. So he signed a three-year deal for $600,000 at a time when players were making $60,000 a year,” Greczmiel explains.

“He shows up at training camp in a Mercedes-Benz. He admitted he was cocky back then, and there was a lot of jealousy and animosity between him and the other players. He was under a tremendous amount of pressure to produce. He was one of my favourite interviews.”

Hampton put up 172 points in an NHL career that lasted 337 games.

The NHL’s only death on the ice

In the helmet-free era, Bill Masterton got sandwiched by two Seals players in an open-ice hit. He fell backwards and smacked his skull on the ice and died in hospital a couple days later.

Greczmiel spoke to three eyewitnesses, who all said it was a clean hit with a tragic result that still haunts them.

“It didn’t seem like a particularly dangerous play. It wasn’t a dirty play. It deeply affected all the players,” says Greczmiel, who acknowledges a purveying dressing-room sentiment of the late-’60s. “If you’re wearing a helmet, you’re not a real hockey player.”

Talkin’ ’bout practice?!

The practices of head coach Fred Glover, who was hired and fired twice by the Seals, often amount to nothing more than scrimmages — in which he participated.

Because practice wouldn’t end until Glover scored, tired players would encourage Meloche to let Coach get one.

“He thought he could still play in the NHL,” Greczmiel says, “Because of that, he resented the players.”

The Seals would watch the well-oiled drills being run by competitors like the Montreal Canadiens and ask for more structure. They also requested video analysis. No go.

The Morris Mott fan club

Utility centre Morris Mott predates John Scott as an ironic NHL hero. Mott never scored more than nine goals in a season in Oakland, but he briefly became a posterboy for the franchise’s mediocrity.

When the Seals rolled up to Madison Square Garden one night the marquee read: “Morris Mott” in big, bold letters, with “and the California Golden Seals” in tiny type.

Mott posters filled the rink, and everyone was laughing — including Mott.

Angels in the stands

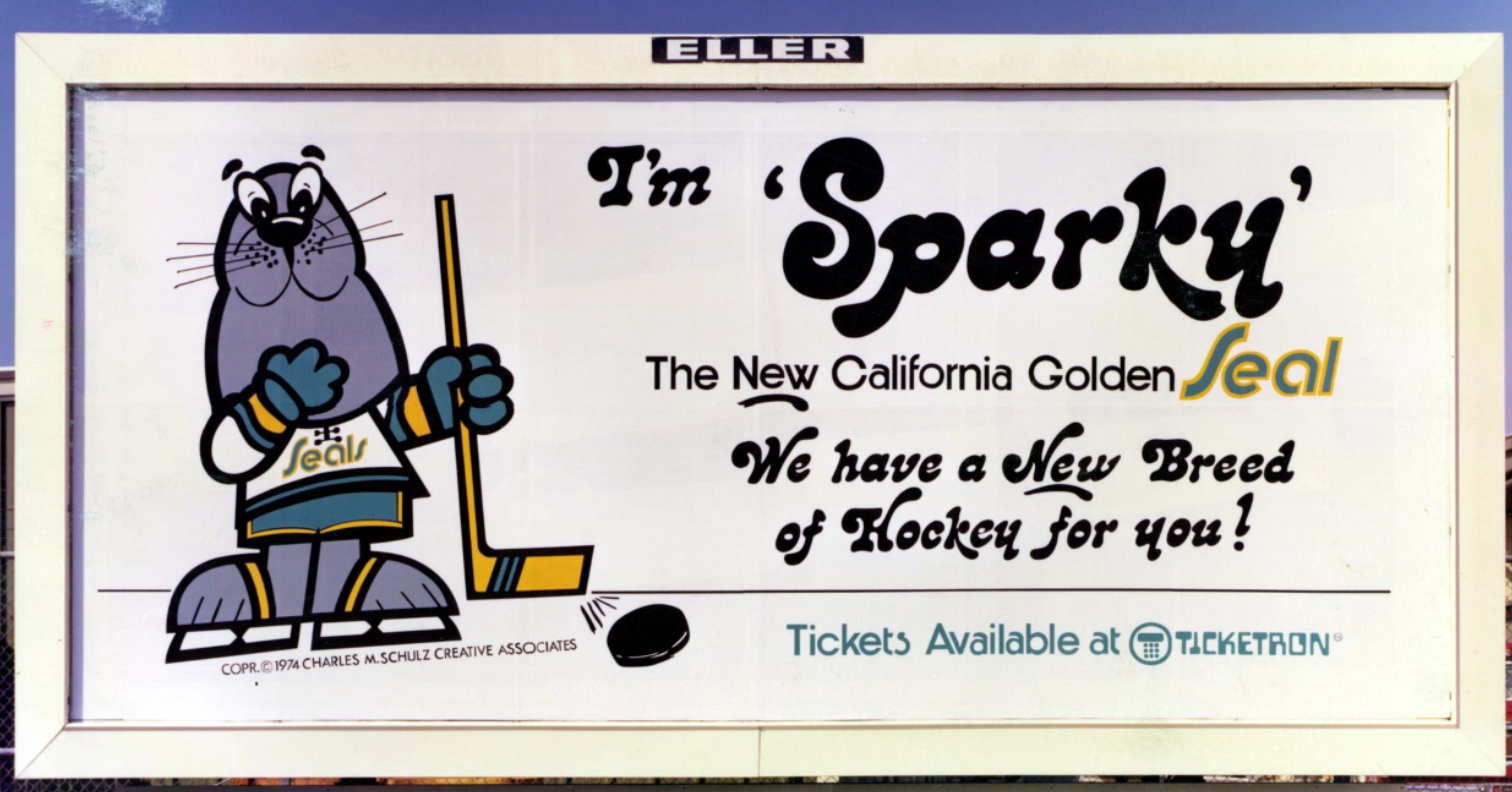

The fans were few but fierce — and included some star power. Peanuts creator Charles Schultz designed the team mascot. Oscar winner Tom Hanks says the Seals were his introduction to the sport:

The Hell’s Angels, whose main clubhouse was in Oakland, not far from Coliseum, were big supporters. The head of the Angels called one player to demand VIP parking for games and other privileges and assured Reggie Leach that if anyone messed with the Seals, the motorcycle gang would have the players’ backs.

The Seals gave us a Top 10 all-time goalie mask

The progressive mask of goaltender Gary “the Cobra” Simmons — which turned heads with its graphic snake paint job — is now in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Coulda been a contender

Among Finley’s mistakes was firing smart hockey men like Bill Torrey from his front office. Torrey would go on to become GM of the expansion New York Islanders and build their ’80s dynasty.

More memorable was Finley’s decision to trade his 1971 first-round pick and François Lacombe in return for Montreal’s 1970 first-round pick and veteran Ernie Hick.

California finished dead last in ’71, allowing the Canadiens to pounce on a future Hall of Famer.

“They traded away the rights to draft Guy LaFleur,” Greczmiel laments. “It’s a snapshot of how not to run a franchise. They could’ve really succeeded.”

In their final season, the Seals drafted a young sniper named Dennis Maruk, who won over fans and put up 30 goals as a rookie. Then the team suddenly and quietly moved to become the Cleveland Barons, a team that would dissolve after two forgettable seasons.

“It was a franchise where everything that could go wrong did go wrong,” Greczmiel says.

They still care

This past January, the San Jose Sharks held a tribute night to their Bay Area predecessors. Greczmiel attended with six former Seals. One wondered aloud, “Will anyone really care?”

As soon as the gates opened, the old Seals’ autograph table was rushed. A crowd six deep bubbled until puck drop, many sporting green and gold throwback sweaters.

“The players were wowed,” Greczmiel says.

(photos courtesy of Mark Greczmiel)