John Tavares sits at his stall, staring at the floor until he can hear the rustling of the reporters and cameramen entering the Islanders’ room and descending on him. He wears the “C” and makes franchise-player money, so this is his team — for better, which has been much of the season, and worse, which is now, on the eve of the playoffs.

His team has just fallen 3–2 to the Anaheim Ducks, a seventh straight loss at Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum. The Islanders are falling down the grid in the Eastern Conference, still will make the playoffs but not looking like a Cup contender. Tavares knows what the questions are going to be. They’re the same ones he’s asking himself.

He has rote answers but not good answers. Nothing he says really deviates from the script that a veteran reads from when spring rolls around and his team is struggling.

“We’re getting chances but we’re not getting results,” he says. “The mistakes we’re making are costing us. We’re trying to simplify [our game], but it’s that time of year. We need to be better. Their goalie made some big saves and I had a couple of chances on the power play, but we have to be better than the goalie in situations like that.”

MORE STANLEY CUP PLAYOFFS: | Broadcast Schedule

Rogers GameCentre LIVE | Stanley Cup Playoffs Fantasy Hockey

New Sportsnet app: iTunes | Google Play

Here the first-person singular and plural are interchangeable. As he goes, so go the Islanders. Of course, that can be said of any of an elite group of players and their teams. Here, though, the dynamic is more complex: As Tavares’s play is going sideways on the ice, the Islanders are disappearing entirely, moving from Long Island to the Barclays Center in Brooklyn next season. Like the merchandise bearing the old-school logo at the team store on the concourse, Tavares and Co. are 40 or even 50 percent off.

The franchise won’t exactly be a memory on Long Island — fans can still trek to Brooklyn to see a game. But the last season won’t be one to remember unless the team can straighten itself out, a task that will fall on the padded shoulders of the guy in front of the cameras. It’s up to John Tavares to lead, to make it happen.

The Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum doesn’t say “faded glory.” It doesn’t really say anything at all. Yes, it’s a historic arena, but it’s not aesthetically pleasing. It is, in fact, an eyesore from the outside, a giant wart emerging from a parking lot by an expressway; it became an architectural blight on the bedroom community of Uniondale five minutes after the ribbon cutting in 1972.

Any history in the building hangs from the rafters. Four Stanley Cup banners from the early ’80s — just for a start. Add one each for Bill Torrey and Al Arbour, the GM and coach respectively of those teams. Add one for every retired number. And don’t even try to count those lesser banners recognizing division and conference wins. Still, all of these stand as reminders that it has been a long time since the Islanders really mattered.

It’s a generational deal: Most fans aren’t old enough to remember those Islanders teams that looked down on the rest of the league. The other Cup-winning teams of that vintage, the Canadiens of the late ’70s and Oilers of the ’80s, overshadow them. Even in their own backyard, the Islanders’ four Cups are eclipsed by the Rangers’ one in ’94. As their long-time announcer “Jiggs” McDonald says, “It’s hard to imagine that a group of players wins four Stanley Cups and flies under the radar, but that’s exactly the case.”

Though a significant block of Islanders veterans found berths in the Hockey Hall of Fame, history has been generally unkind to them, even uninterested. Take the election of Clark Gillies to the Hall — critics will often cite his name when they complain that the committee lets in too many very-good-but-not-great players. Those who were on the scene will tell you that Gillies was in fact the leader of those four championship teams, even though Denis Potvin wore the “C.” If something had to be said, he said it. If Torrey or Arbour ever needed to read the room, they looked to him.

Still living on Long Island, Gillies has watched Tavares since he joined the Islanders after the team selected him first overall in 2009.

“There’s no question about John being the leader on this team, but this team and the times are entirely different,” Gillies says. “No one would ever claim that I was the best player or the most valuable guy [on the Cup-winning teams]. We have a Norris winner with Denis Potvin. Bryan Trottier wins a Hart and Mike Bossy is a 50-goal scorer. Butch Goring wins a Conn Smythe. We had a group of guys who were as good as anyone in the league at what they did. John’s situation isn’t like that. There are some good players around him, like Kyle Okposo, who’s really coming into his own. But no one is up there with John.”

Gillies believes Tavares was the league MVP when the Islanders made it to the playoffs in the lockout-shortened 2013 season — and more valuable than any one player was for the Islanders’ dynasty. “When he’s hurt [as he was last season], the team misses the playoffs,” says Gillies. “It’s a top-heavy lineup that way.”

By Gillies’s reckoning, the dynamics in the league have changed so significantly that his own approach to a leadership role might no longer work.

“We had a group of core players in the top half of our lineup who played together for a decade or so, and that doesn’t happen anymore, practically anywhere. Someone in John’s position isn’t going to know everyone the way I knew my teammates. [Someone who leads a team now] has to do it mostly by example with their work ethic. I think that’s always been there with him—there’s no one who’s more committed to paying the price to be a better player. I really believe when they gave him the ‘C,’ his work ethic became the team’s.”

When Tavares was a rookie in 2009, he moved into the home of teammate Doug Weight — it’s not part of the collective agreement, but the teenager-as-lodger has become standard procedure with kids straight out of the draft. Weight noticed the pressure Tavares put on himself from day one and continues to see it every day as an assistant coach. Weight says he has skated with and against and has coached guys who made themselves better players since first arriving in the NHL in 1991, but no one who made himself a different player — until Tavares.

“When John came in, his reputation preceded him [as] being the exceptional player [in the Ontario Hockey League] and a first-overall pick with amazing skills,” Weight says. “But there were questions about him. Was his skating good enough? Was he going to be able to get to the net? John rallied around those questions and made himself better. He changed his skating—broke it down, almost started from scratch—and now what people saw as a weakness has become a strength. He’s in the top 20 percent of guys in the league for explosion and strength on the puck. You look at Sidney Crosby or Jonathan Toews as rookies, and five years into their careers they’re the same player only stronger. John, though, is a different player.”

Some changes in Tavares are more organic — seemingly so, anyway. Although Crosby was snickered at for being obsessed with the game, trying to find ice on off-days, and Toews was saddled with the “Captain Serious” handle, Tavares might have been even more focused than either of them. Weight says that he tried to influence Tavares, but the overall message was the polar opposite of the one he received from Rangers’ teammates back in ’91.

“We had veterans like Brian Leetch and Adam Graves, and I learned from them about focusing on the game around a lot of distractions,” Weight says. “For John, that focus was always there. He had to learn to relax and get away from the game. From the age of 14, it had always been, ‘How am I going to get better?’ He had to not be all about hockey 24/7 so that he could see the game with fresh eyes sometimes. And it’s like everything John does—he adapts and makes changes and does what’s necessary to be great.”

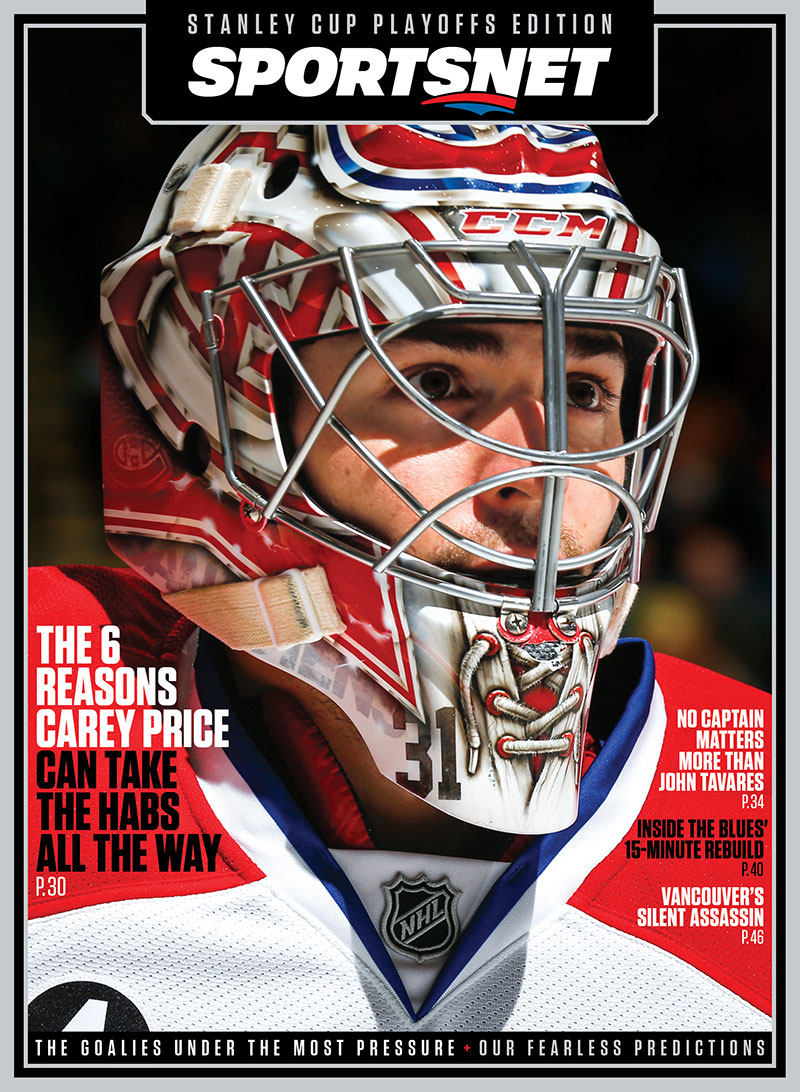

Sportsnet Magazine Stanley Cup Playoffs

Sportsnet Magazine Stanley Cup Playoffs

Edition: The six reasons why Carey Price can take the Montreal Canadiens all the way. Download it right now on your iOS or Android device, free to Sportsnet ONE subscribers.

Changing himself on the ice was a challenge that would break many, including a few $7-million players, but Tavares made it look relatively easy — “Embrace the pain” is the mantra in the Islanders room, and no other player on the team has embraced it more. Change off the ice, though, was something he says he had to wait out, drawing lessons from his mistakes. As a junior in Oshawa and London, Ont., Tavares earned a reputation as something less than a team player — maybe unfair, but understandable given the pressure he faced as an underage wunderkind who grew up in the public eye. Compared to the likes of Crosby, Toews and Steven Stamkos, he was socially awkward, a bit of a hockey-playing bubble boy. That’s hard to imagine now for those meeting him for the first time.

“I’ve had a chance to mature,” Tavares says. “There are things that I would like to have dealt with differently, but I learned from a lot of veterans I’ve played with. Doug Weight was like an older brother to me. He couldn’t have been a better example of what I needed. And really, through him I realized that it’s not hard to reach out and say a few words, to find a way to make your teammates better and push harder. I’ve grown up, and we have a lot of young players who are going through the same thing I did. If I can reach out to them and help them along, that’s my role as a captain and a teammate.”

The one Islander who benefits most from this outreach is Ryan Strome, who moved in with Tavares at the start of the season. In many ways, Strome seems better cast as a little brother to Tavares than Tavares was to Weight. Both are from Mississauga, Ont. Both played for the Toronto Marlboros. Both were first-rounders. Both have amazing puck skills and game instincts that can’t be taught. Both are natural centres, although Strome has moved onto Tavares’s left wing. Yet it would be hard to find two young men whose temperaments are more different. Says Weight: “John was naturally quiet, a model student living in the family home, great with our kids. Ryan’s a fun-loving kid who would be a handful—he’d be getting grounded.”

The two already knew each other pretty well by the time they became roommates. Not long after he was drafted by the Islanders, Strome was tagging along behind Tavares.

“John’s a role model to me,” Strome says. “The past couple of years, we got to work out together in the off-season, and I’ve had a chance to get to know him better and appreciate his commitment. If I do half the things that he does, I’ll be a better player. Watching him, studying video with him, I’m trying to think the game the way he does and emulate what he does.”

The afternoon after the loss to Anaheim, the Islanders have another chance to break the losing streak on home ice, but not an easy one against the Red Wings. Less than two minutes into the game, it became a lot less easy, with the home team falling behind 2–0 as Jaroslav Halak fumbled away the first two shots he faced. Turns of events like this can be dispiriting even for a team on a good run, and will almost inevitably suck the life from 99 out of 100 players in the league. It thus falls to the Islanders’ one-percenter to shift the paradigm.

Tavares wills himself to be better than he had been the day before against the Ducks. Not even four minutes in, he pounces on a turnover at the Red Wings’ blueline. With his linemates heading the other direction, he skates in alone, at best one-on-two and more like one-on-three, with Detroit reinforcements doubling back. Wings defencemen Danny DeKeyser and Kyle Quincey give ground — rather than chasing Tavares, DeKeyser tries to push him out on the perimeter. It looks like Tavares is just buying time for a line change when he starts to drift aimlessly to the boards on his left, even more so when he overskates the puck. In fact, he’s just diverting DeKeyser and allowing Strome to skate into his wake with a wide-open lane to the net. Strome fires a shot that Petr Mrazek stops, leaving a rebound that the kid gleefully cashes in.

Tavares will wind up with three assists and the first star in a 5–4 win over Detroit. Strome’s goal, though, was the turning point—improbably, it made the game 2–2 at 4:01. “John led and I followed him,” Strome says after.

In that one shift and one sentence, a 21-year-old protege captured all things: his 24-year-old mentor, their team, its prospects in the playoffs and the times.