It’s a familiar strategy, one that’s been around for longer than I’ve been alive: Middling-to-bad teams realizing that they’re stuck in a rut they can’t get out of, and deciding that the best road back to success is a few years in the basement collecting top draft picks.

When the strategy works, the results can be breathtaking. Chicago has won two Stanley Cups in the past five years, largely thanks to top picks Patrick Kane and Jonathan Toews. Los Angeles has two Cups in four years, and the team’s two most critical players are early picks Drew Doughty and Anze Kopitar. Pittsburgh won it all in 2009, and probably would have repeated since if not for spectacularly bad goaltending come playoff time; their team was built on myriad high picks .

The problem is that not all drafts are created equal. This is especially true at the very top end. Sometimes, the team with the first-overall pick has a chance at Sidney Crosby or Alex Ovechkin; sometimes there’s even an Evgeni Malkin or Tyler Seguin sitting there at No. 2. But that isn’t always the case.

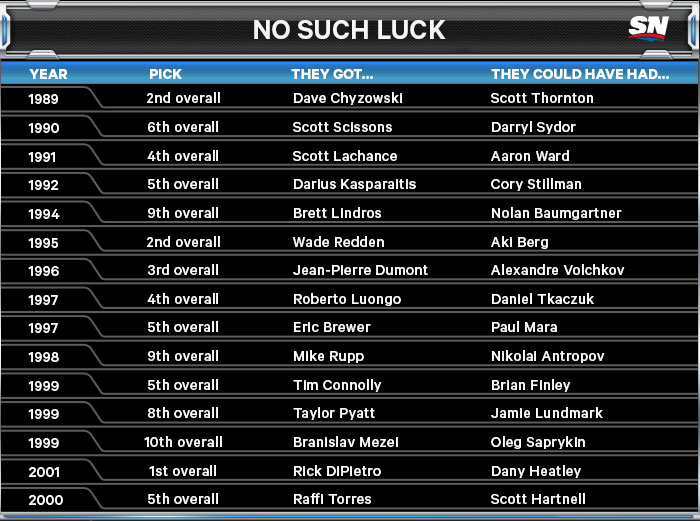

The New York Islanders are a great example. Part of the reason the franchise has had such a bad reputation post-dynasty has to do with ownership and bad management, but a significant part has to do with the draft in the years the team was bad enough to be collecting top picks. Between 1989 and 2000, the Islanders had 15 top-10 selections. There are some pretty obvious managerial mistakes—the decision to trade Roberto Luongo to draft Rick DiPietro over Dany Heatley is a whopper—but the biggest part of the equation is high picks in weak drafts. That’s evident when we look at the picks made immediately following New York’s selection.

Yes, the Islanders were a poorly run team with uncertain ownership. But they might have gotten away with it if the talent at the draft was a little better. New York wasn’t generally picking first overall, though, and that’s the place we see some of the biggest year-to-year swings.

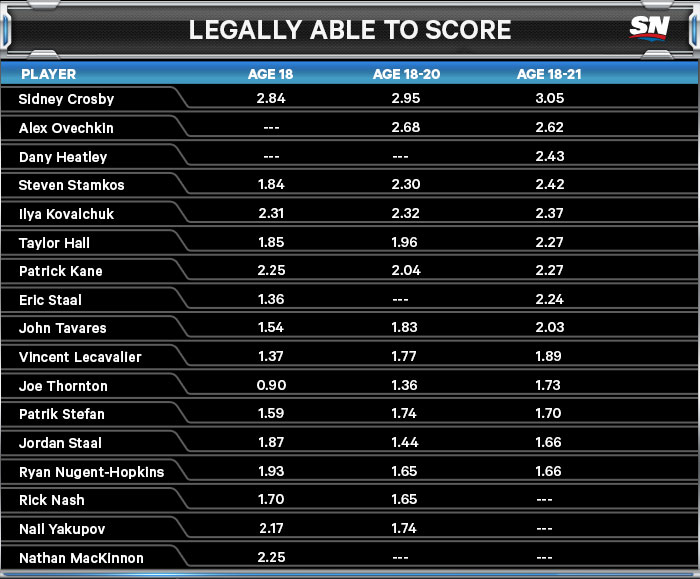

I wanted to identify how big those swings can be and determine whether or not they are predictable in advance. I decided the best way was to key in on the top forward in each draft (if a goalie or defencemen went first overall, I substituted the first forward picked) to eliminate positional considerations. I needed to settle on a single metric to rate performance, and opted for even-strength points per hour, based on raw numbers from the NHL’s official website (which goes back to 1997-98). To make things fair, I looked at each player’s performance between the ages of 18 and 21:

The dashes indicate a year is missing, either because a player stayed in college (Heatley), has yet to play that season (MacKinnon, Yakupov) or thanks to the 2004-05 NHL lockout (everyone else). Thornton deserves special mention here; Boston used him in a bizarre way that crippled his scoring numbers early in his career.

Even though we don’t usually think of scoring in these terms, the gap is obvious. Crosby was a legitimate top-three NHL scorer based on his average performance over his first three seasons. The gap between Crosby and the next tier is roughly one point every two hours; players at this level (Ovechkin, Heatley, Stamkos) are still exceptional, though, scoring at a top-15 clip on average over their first three campaigns.

But then there are the guys at the other end of the scale. Nugent-Hopkins’s offence in his first three seasons is terrible by first-overall standards; it’s only a shade better than half of what Crosby posted. Where Crosby was a franchise scorer out of the gate, a Nugent-Hopkins, Jordan Staal or Stefan were below-average second-liners in terms of even-strength points.

This is the kind of chart that goes some way toward explaining why the Edmonton Oilers have yet to significantly turn their fortunes around. Hall is a legitimate No. 1 pick, a little better than the average, but Nugent-Hopkins is at the bottom end of the scale over his first three years and through two seasons there are some troubling signs with Yakupov.

The year-to-year variance is what makes the 2015 Draft so special. Connor McDavid’s name is whispered in the same awestruck tones that scouts used when they described Crosby a decade ago. “Maybe McDavid’s numbers at 16 won’t quite be there with Crosby’s at 16, but his upside is higher,” a scouting director with a Western Conference team told Sportsnet’s own Gare Joyce last year. “Skating is what separates him. Crosby’s greatest asset is his strength on his skates. McDavid has that same strength but he’s even harder to push off the puck because he’s moving faster.”

Never mind better; if McDavid can even manage being similar to Crosby he could be worth two or even three lesser first-overall picks.

That potential opens up some intriguing possibilities. Imagine for a moment that McDavid is as good as the hype, and further that the Calgary Flames (who on paper seem bound for a finish near the bottom of the league) were to win the NHL Draft Lottery next summer. In this scenario, arguably the Flames could get a better return on one first overall pick than the rival Oilers did in that slot for three consecutive seasons. That’s a terrifying thought for Edmonton; a thrilling one for Calgary.

And therein lies the rub when rebuilding through high draft picks. It isn’t enough for a team to just be in the right place, in this case picking first overall; it also has to be there at the right time to attain maximum value.