It was not, to greatly understate it, a warm welcome.

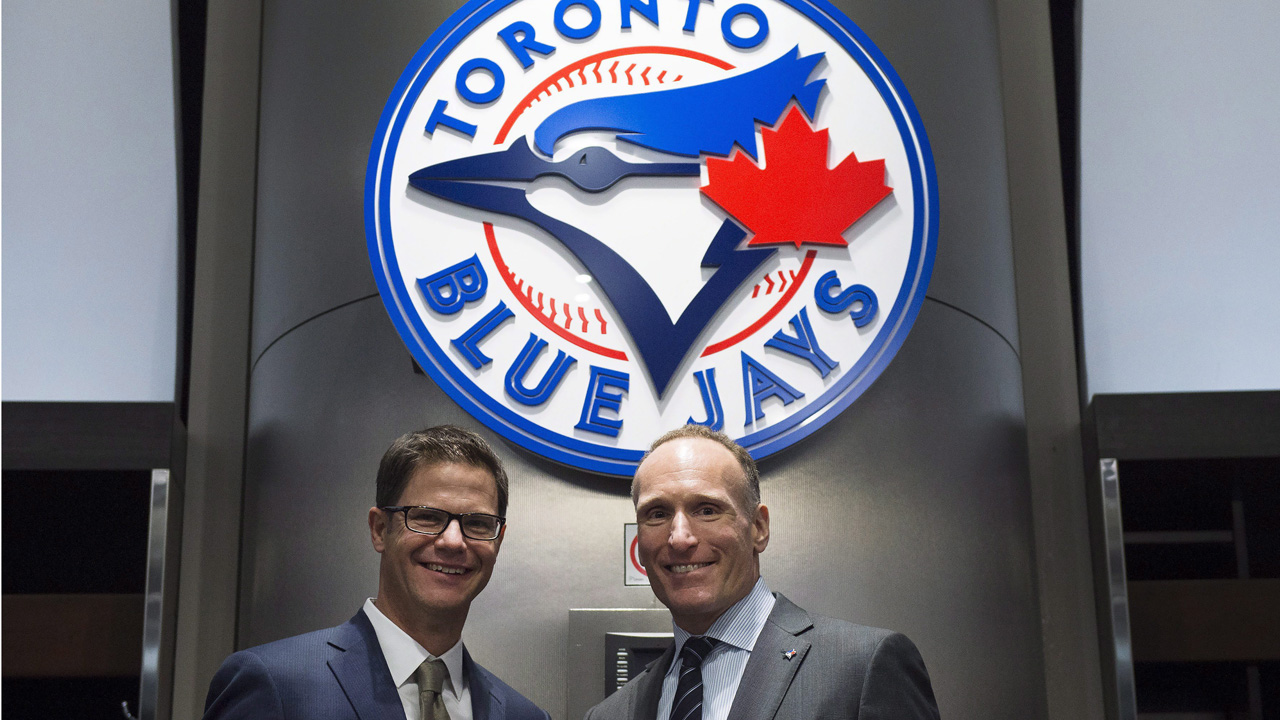

On Aug. 31, 2015, Mark Shapiro was announced as the next president of the Toronto Blue Jays, and the fans of that suddenly red-hot baseball team skipped right past the getting-to-know-you part. Here was a fairy tale playing out right before their eyes, a club transformed at the trade deadline through the wizardry of Alex Anthopoulos—Canadian, former Expos fanboy, in every way one of their own—now rolling toward its first playoff appearance since 1993.

MEET THE PREZ: Watch Stephen Brunt’s TV special First Impression: The Mark Shapiro Story, April 17 at 12:30 p.m. ET, just before the Blue Jays take on the Red Sox

And here was the new guy, brought in to replace Paul Beeston, but for all intents and purposes the person who would now shape the Blue Jays in his own image on and off the field, hailing from Cleveland of all places—the name of the town uttered as though the Indians, not the Blue Jays, had been a baseball punchline for the previous 22 seasons.

Shapiro was instantly cast as Skeletor, as Darth Vader. Cue the heel’s walk-out music.

And why did he pronounce his name that way?

It didn’t help that Shapiro lacked Anthopoulos’s ordinary-guy-ness; it didn’t help that when speaking in public, he tended to sound like a PowerPoint presentation, like one of those books that tells you how to be a better boss.

But the deck was stacked against him, regardless. “I’m not sure I could have been any more thoughtful,” Shapiro says. “I’m not sure I could have been any more culturally sensitive and aware. I’m not sure I could have embraced the place I was coming to any more. There were certainly maybe some things I did that didn’t help to endear me to people. But people were looking for things to not like about me rather than things to like about me. I view those as circumstances. It’s the situation I walked into. Really, if you look at what happened, nothing was my choice. Nothing was about decisions I made. I was walking into a situation that dramatically changed from when I made the decision to come here to the time I started working here. The circumstances and situation were something that I didn’t have control over, and that was something I had to manage through.”

Shapiro admits that the wave of hostility was such that, for his family’s sake, he went so far as to question whether he had made the right decision accepting the Toronto job.

The atmosphere is a little less charged now. The anger, to a degree, has abated. The Jays assembled in Dunedin this spring looking very much like the heroes of last autumn, and keen baseball observers couldn’t help but approve of some of the moves made by Shapiro and his general manager Ross Atkins—not flashy acquisitions, not top-of-the-market signings or franchise-altering trades, but savvy personnel decisions designed to provide depth and shore up the foundation of a team already built to win in 2016.

Beyond this season, though, it’s going to get tricky, with an aging roster, some significant contract obligations, a farm system that has been thoroughly strip-mined and a market that has suddenly remembered what it’s like to support a winner. As the Jays make their way down that road, the question that hasn’t really been asked is going to be answered: So just who is this Shapiro guy?

He is the dutiful eldest son of a significant figure in the business of baseball, Ron Shapiro, a Baltimore-based lawyer who got into the player-representation business after helping Brooks Robinson negotiate his way out of a difficult financial situation. Ron’s clients would eventually come to include some of the stars of the game, among them local heroes Cal Ripken Jr. and Eddie Murray. Mark Shapiro grew up in a household where the same players he had been cheering for at Memorial Stadium were suddenly guests at the family dinner table.

(Oh, and about the name: Why is it pronounced Shap-EYE-row instead of the usual Shap-EAR-row? When his father’s parents arrived at Ellis Island from what is now part of Ukraine, their last name was anglicized. There were Schapiros and Shapiros, and one group that ended up settling around Philadelphia—where Ron grew up—and Cherry Hill, N.J., was saddled with the unusual pronunciation. According to Shapiro, that’s the whole story, though it’s also the question he answers more than any other.)

Ron was and is a towering influence in his son’s life. The son grew up in privilege—aware, and perhaps a bit guilty, that he was growing up in privilege—attending prep school and Princeton University, where he played on the offensive line for the football team. “I was a classic eldest child,” he says. “I definitely did have a few transgressions. But I was a kid who was really conscientious and wanted to achieve and wanted my parents to approve of what I was doing.” (When he was 12 years old, Shapiro put two slogans on his bedroom door: Vince Lombardi’s famous “commitment to excellence” quote and the words “keep perspective”—so an old soul at least, if not an out-and-out square.)

Shapiro’s parents divorced while he was in university. One by-product of the split is that he became extremely close with his younger siblings, brother David, who is the president and CEO of Mentor, a national not-for-profit in the U.S., and sister Julie, who is married to NFL coach Eric Mangini.

Instead of going to law school—“I think it would have made a lot of sense to my dad, and I thought a lot about it, but I just didn’t want to be a lawyer”—he opted to try something different, first taking a position with a house builder in Southern California, in which he learned the business from the construction site on up, and then a job in New York City as an analyst for a retailer.

Neither was the right fit. Not unlike Anthopoulos (albeit with the not-insignificant advantage of name recognition and an Ivy League pedigree), he decided that he really wanted to work in baseball, so he sent cover letters and resumés to the 26 major-league teams, offering his services in any capacity. Eventually, one replied: the sad-sack Cleveland Indians—an organization poised for a great leap forward under the leadership of John Hart, though on the surface, it didn’t look that way.

In May 1992, Shapiro’s father came to Cleveland to visit him there for the first time. His workspace was a cubicle outside Hart’s office. That night, the Indians played the Kansas City Royals in cavernous Municipal Stadium, capacity 70,000-plus. The announced attendance was 8,000, but there were really only about 1,500 people in the stands. In the empty bleachers, two vendors sat watching the game, drinking their own beer. “My dad looked around and said, ‘Are you sure this is what you want?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely.’”

Meanwhile, to the north and east, Toronto looked like the Emerald City by comparison. The Blue Jays were on their way to their first World Series, and whenever they came to Cleveland, Toronto fans unable to get tickets at the SkyDome flocked south to watch their team.

What followed was one of the great turnarounds in modern baseball history. Hart and Dan O’Dowd rebuilt the Indians organization, drafting brilliantly and pioneering the practice of signing arbitration-eligible young players to long-term contract extensions. Jacobs Field opened, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame opened, and with the Browns gone and the Cavaliers terrible and playing in suburban Richfield, it was the Indians who caught the wave of a Cleveland renaissance. Big-name free-agent signings were eventually added to the homegrown-player mix. Every year, it seemed, they were in the playoffs. Every seat was sold every night.

Then ownership changed in 2000, and Hart left the following year, and it was clear his timing was impeccable. “We all knew there were challenges coming,” says Shapiro, who took over the reins of the team at 34. “But none of us knew how big those challenges were.”

The team, because of its success, had been drafting late. The farm system was depleted. The major-league roster was aging. “We were nearing a tipping point, going toward that cliff,” Shapiro says.

“But nobody knew it, because the backdrop was eight straight years of incredible success, seven years in the playoffs, two American League championships and World Series appearances. A decision in Cleveland had not been made with anything other than winning in mind for seven or eight years. Free-agent signings, trades. It was all about winning.”

Now that was going to change, and Shapiro would be the unpopular face of it, first dealing away Roberto Alomar, then, with the Indians still in contention, trading away the team’s No. 1 starter Bartolo Colon to the Montreal Expos in return for journeyman Lee Stevens and three anonymous players who were identified in the first news reports simply as “minor-leaguers”: Grady Sizemore, Cliff Lee and Brandon Phillips.

“It was a chance to make what was a very good trade. It was definitely the best trade I ever made. But as I sat at my desk the night before, I was thinking, ‘Tonight, I’m going to make my first big decision, and I’m going to let down every constituency I have. I’m going to crush the fans. They’re not going to understand. I’m going to walk in the clubhouse and tell the coaching staff and the players that we made a move that’s not about winning. And I’ve got to look at the rest of the office, the ticket sellers and the marketers and tell them that your job is about to get a lot harder.’ I call that the blank-stare period. I got a lot of blank stares. I talked about the plan we had to be good within three years, which was overly ambitious. It was a little naive to say that. It was a little ignorant of me. But in the end, we did it.”

The Indians were indeed back in contention by 2005, and Shapiro wound up twice being named baseball’s executive of the year.

Getting there, though, he learned what it felt like to be hated. “I got yelled at walking to lunch,” he remembers. “I got death threats. And the day I made the Colon trade, I drove out of the ballpark and there was one guy waiting for me in the parking lot, holding a sign. It said, ‘Shapiro Bobblehead Night June 26, 2002—No Spring Needed.’”

So it’s a new team, a new city, a new country.

But Shapiro has been here before. And he has grown a very thick skin.