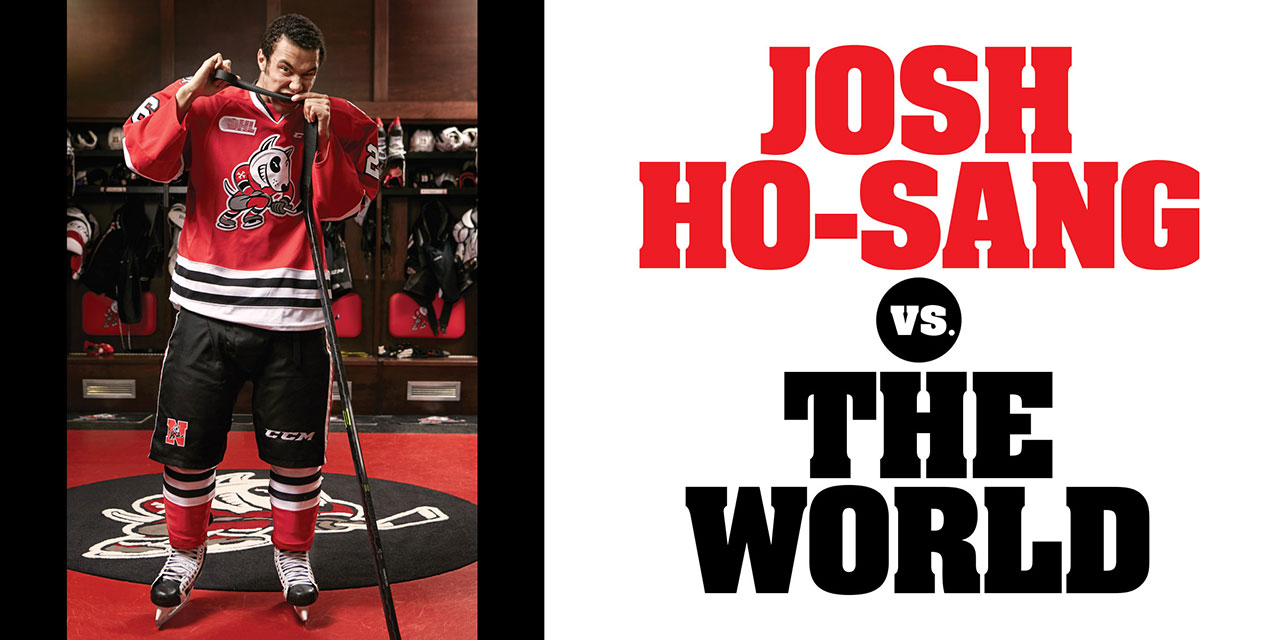

The New York Islanders prospect is loaded with talent, but how will his swaggering style play in the team-first NHL?

By Arden Zwelling in St. Catharines, Ont.

Photography by Andy Vanderkaay

wo hours to puck drop on a Saturday night in downtown St. Catharines, Ont. Red-blazered ushers make busy, lugging boxes of programs and giant plastic bags of popcorn back and forth through the Meridian Centre, home of the Niagara IceDogs. They edge toward the side of the concourse as teenage hockey players in T-shirts and hoodies stream past doing high knees and lunges, physically preparing for tonight’s game. The business of junior hockey, as usual.

wo hours to puck drop on a Saturday night in downtown St. Catharines, Ont. Red-blazered ushers make busy, lugging boxes of programs and giant plastic bags of popcorn back and forth through the Meridian Centre, home of the Niagara IceDogs. They edge toward the side of the concourse as teenage hockey players in T-shirts and hoodies stream past doing high knees and lunges, physically preparing for tonight’s game. The business of junior hockey, as usual.

But one thing stands out. There’s a lone IceDog lagging behind, a slender kid in black sneakers, compression shorts and a grey sweatshirt, its hood pulled over his bulky headphones, his hands tucked into the sleeves like a chilly child’s at the skating rink. His effort level hovers somewhere slightly south of interested as he half-heartedly does his thing several steps behind the rest of the group. When the routine is through, his teammates file off to the dressing room to get ready for the game, but he stays on the concourse, walking around and fiddling with his phone while the Zamboni makes its rounds on the ice below. About an hour later, when the IceDogs spill out for their pre-game skate, he’ll be the last one on the ice and the first one off of it, after stickhandling for a bit, taking a couple shots on an empty net and mostly ambling around. The rest of the team stays out until the buzzer goes.

His name is Josh Ho-Sang. Just 19 and widely regarded as one of the most naturally gifted players in the Ontario Hockey League, he might go down as one of the NHL Draft’s greatest steals, at 28th overall, where the New York Islanders selected him last year. He might be part of a dynamic, reinvigorated franchise that is moving to Brooklyn next season and building one of the NHL’s most feared cores of young players. He might be a truly special, unfathomably skilled talent for years to come. Or he might be a cautionary tale. He might end up squandering his exceptional talent, as many coaches have warned him along the way, if he doesn’t conform and stop stubbornly doing things his way. He might be a spectacular disaster.

We’ll see. All that can be certain is that Ho-Sang will definitely be something. He hasn’t played a minute in the NHL and 26 teams thought better of taking him on draft day (Vancouver passed twice) last summer, but he’s still one of the league’s most talked-about prospects, not only for his breathtaking play on the ice, but for his hubris off of it. He’s called out Hockey Canada, saying he’s insulted at his exclusion from various national teams over the past two years. He’s said that the governing body is afraid to invite him to development camps because he’ll play so well that they’ll have no choice but to put him on national teams. He’s said that he’ll be the best player in his draft class within the next three years, better than each of the 27 taken ahead of him. He’s caused quite a bit of commotion.

One wonders what the NHL’s moral outrage police will make of Ho-Sang when, and if, he arrives. If Patrick Kane (one of Ho-Sang’s favourite players) is too brash, and Tyler Seguin is too self-centred, and P.K. Subban celebrates too much, what will they do when confronted with Ho-Sang, a player who, after scoring an end-to-end goal earlier this season on which his teammates might as well have stood on their skates and watched, beelined directly toward the opposition bench so he could perform a shimmy shake in front of it? A player whose outspoken, contentious comments about his abilities, his place in the game and his perceived mistreatment throughout his career stand in stark contrast to the team-first, me-last culture that hockey’s most diehard supporters aim to instill? Is Ho-Sang a selfish malcontent? A problem child? Or is he just a confident kid being himself?

Ho-Sang, who never wanted for new equipment and went to a private hockey school in Toronto, says he plans to help other kids realize their dreams with the wealth he hopes to accrue in the NHL. “There are kids out there worried about eating.”

“When you boil it down, all I’ve said in the media is that I believe in myself, that I have dreams. I don’t know what’s wrong with that,” Ho-Sang says. “People will find what they want to find in what I say. I just speak my mind. If people want to make me seem like an asshole, go ahead. It’s cool.” There’s something endearing about Ho-Sang’s outlook. The brazen self-assuredness; the cavalier cockiness; the willingness to speak his mind, even when directly affronting those who could hold his career in their hands, out of principle and a determined certainty that he’s right; the undying belief that he’s going to be great. In a way, it makes you want to root for him to succeed. And it makes you wish you were a bit more like him, too. “I’ve heard from at least a hundred people who have said, ‘You gave me confidence to believe in myself,’” Ho-Sang says. “Being a teenager and calling out Hockey Canada and saying I want to be great in the NHL—I do it so people can see that I have dreams. Even if I don’t achieve them, maybe it’ll give people inspiration to chase their own dreams. I think a lot of people take something from my confidence. They’re like, ‘Hey, I could be like him.’”

Ho-Sang grew up on the border of Thornhill and Toronto in a home that was essentially a daily course in multiculturalism. His mother, Ericka, is Jewish and from Santiago, Chile. His father, Wayne, is Christian and from Kingston, Jamaica. Erika’s mother is part Russian and part German, while her father is Spanish. Wayne’s parents are Jamaican like him, but his grandfather—Ho-Sang’s great grandfather—was from Hong Kong. And if you’re still with us, we might as well mention that Ho-Sang’s godmother is Greek and a strong presence in his life. This familial melting pot meant that as a child Ho-Sang celebrated both Christian and Jewish traditions, running back and forth between the homes of his grandparents during the holiday season. He learned Spanish, took part in Greek traditions with his godmother, and even developed an interest in Buddhism when he was in high school.

Along with the many different perspectives colouring his upbringing, Ho-Sang was raised to ask questions, to thoroughly argue his side of the matter in any dispute. This may not have manifested itself more perfectly than when his parents initially tried pushing him toward tennis (father Wayne loves the game and works as a tennis pro) and Ho-Sang wouldn’t stop using the racket to stickhandle tennis balls around the court. By 13, he was enrolled at Premier Elite Athletes’ Collegiate in Toronto’s Downsview Park, where he was on the ice nine times a week between classes, passing and shooting for hours on end, repeating the same drills over and over until they were second nature, laying the foundation for the incredible puck-handling abilities he demonstrates today. He played minor midget AAA with the Toronto Marlboros, starring on a line with Connor McDavid (perhaps you’ve heard of him) and scoring 31 goals and 79 points in 30 games in his final year before being drafted fifth overall into the OHL by the Windsor Spitfires. Over the next two and a half years, Ho-Sang played 141 games for the Spitfires, scoring 49 goals and 148 points before the rebuilding club traded him this winter to Niagara, where he put up 54 points in his first 44 games. Everywhere he’s gone, he’s produced.

This is his biggest gripe with Hockey Canada. Despite scoring 32 goals and 85 points in 67 OHL games last season, Ho-Sang wasn’t invited to audition for Canada’s under-18 team last year or world junior team this past fall. “We talked a lot about Josh,” said Hockey Canada’s director of player personnel, Ryan Jankowski, in December. “And like a lot of ’96-born players, even first-rounders, they’re not quite ready for this event, this stage.” Instead, Ho-Sang watched the world junior squad win gold in his hometown while he rode the bus between away games with the rest of the IceDogs. The first and last time he played for Hockey Canada was at the World Under-17 Hockey Challenge in 2013, on Team Ontario along with a number of the players who would eventually make up this year’s world junior team. He played limited minutes but still managed five points in his five games, including three goals, and finished plus-five. But his team finished sixth in the tournament after falling to Quebec in their final game of the round robin, the first time in seven years that Ontario had lost to Quebec and failed to reach the semifinals. As Ho-Sang tells it, the coaching staff blamed him for the loss. “They got mad at me and said I don’t play hockey properly, that if I don’t change my game I’m gonna end up playing in the coast [the ECHL],” Ho-Sang says. “It’s like, you guys are losers. You’re trying to blame the whole thing on me; you’re saying I’m uncoachable and all this stuff. And ever since then I haven’t been invited to a Hockey Canada camp. But you have the best team in the world on paper, and, what, we lost because of me?”

Ho-Sang says he was told that he played too selfishly, that he didn’t operate within the team’s systems. It wouldn’t be the last time he heard it. At the NHL Combine Ho-Sang was asked to interview with just 18 of the league’s 30 teams, a conspicuously low number for a player of his talent. Rumours swirled that Ho-Sang was on some teams’ do-not-draft lists, and that his attitude and maturity had turned many GMs off. Some of his interviews were essentially confrontations. He says that he walked into one room and the first thing a team said to him was “Why are you so shit defensively?” Ho-Sang asserted that he wasn’t, citing his plus-minus and his even-strength points. “They just kept going on about how I don’t play defence and how selfish I am. I just kept telling them I don’t get scored on. I have the puck. We’re good. I may not be in the position you want me to be in, but I don’t get scored on,” Ho-Sang says. “And they’d say, ‘Well, you will at the next level.’ But how do they know? That’s like saying it’s going to rain tomorrow. You may have a lot of the facts, but you still can’t control the weather.”

You get a sense of why Ho-Sang feels so embattled. And you get a sense of why some teams want nothing to do with him. His reticence to change; his unfailing belief in himself; his combativeness when challenged; his conviction in never being wrong. It all rubs people the wrong way. But even now, almost a year later, Ho-Sang looks back on the combine with defiance. “It’s ridiculous. If there were cameras in the room, people would be like, ‘Why are you talking to kids like this?’” Ho-Sang says. “They try to antagonize you; they try to hurt your feelings; they try to get in your head; they try to make you feel like shit. But, like, I’m gonna live and die anyway, you know? So I play their game right back.”

With all the commotion swirling around him, it can be easy to overlook how exceptional Ho-Sang’s on-ice talent is. And how hard he’s worked. Ho-Sang is on the smaller side of today’s hockey player, at just under six feet and a slim 170 lb., but he’s incredibly quick and the puck seems glued to the blade of his stick as he weaves his way through defenders. He attracts so much attention from opposing tems, who often send at least two pursuers to try to contain him, that it opens up opportunities for his linemates. And Ho-Sang is so good with the puck that he weaves, scanning for the open man and dropping a saucer pass over a stick or chipping a puck ahead through a defenceman’s skates and into open space. Every time he has the puck, he creates. And he plays with a confidence that’s rarely seen from a player his age. “I think I could be an 80-point guy in the NHL,” Ho-Sang says. “I’m too good of a passer to not get points. Every night I make at least 10 passes we can score on. Even if that gets limited to two in the NHL, you’re playing with guys who are 100-percent guys. Like, on those two passes, they’re scoring.”

Ho-Sang says he sees himself scoring 50 points as an NHL rookie and reaching 80 shortly after that. He wants to have $100 million in the bank or close to it by the time he’s 35. Then he wants to start helping people, visiting children’s hospitals, creating opportunities for disadvantaged youth who haven’t been as fortunate as he has. Ho-Sang never had to pine for the latest skates; if he needed new equipment, his parents paid for it; if he wanted to go to a hockey school, he got to go to the hockey school. “Nothing’s been hard about my life. Nothing,” Ho-Sang says. “There are kids out there worried about eating, not about having to do an interview or how they’re going to play. So those are the people that I want to help out. I want to be world changing.”

Super Talent Ho-Sang was taken fifth overall by the Windsor Spitfires in the 2012 OHL draft. In 185 games of junior hockey (he’s now with the Niagara IceDogs), he’s put up 202 points—61 goals, 141 assists.

This is what gets lost in Ho-Sang’s quotes when they’re in print—how intelligent he is. He’s not being brash and cocky because he doesn’t know any better. Quite the contrary. He knows exactly what the hockey world wants him to say and how it wants him to act. He’s well aware of the filtered, cliché-spinning persona he can wear publicly to make his life easier, and he’ll disinterestedly show that to you if you bore him enough. He’s well aware of how the professional sports public perception game is played and how to use it to his advantage. He just doesn’t want to. For one reason or another, he’d rather be loud; he’d rather try to get under someone’s skin; he’d rather fly in the face of how people want him to be. It could be a statement, a rage against the machine, or it could be for his own entertainment. After all, he’s 19 years old—he might just be bored.

Long after the arena had cleared out on that Saturday night in St. Catharines, Ho-Sang walked back onto the concourse where he’d lackadaisically warmed up hours earlier, and met a man sitting in the ninth row of seats behind the net on the south end of the building. The IceDogs had lost, albeit through little fault of Ho-Sang’s. He had a brilliant third period, drawing a key penalty, setting a screen on one goal and scoring one of his own as Niagara roared back to tie the game. On Ho-Sang’s goal he took the puck at his own blueline and charged up the left wing, vigorously stickhandling through defenders and into the opposition zone. He looped behind the net and suddenly stopped, spraying ice chips everywhere as he left a defender spinning. He reversed back around to the left side, got a screen, and fired. As the puck went in, Ho-Sang bent to a knee and touched his glove to the ice before jumping into the boards and fist pumping all the way back to the bench. He looked as alive as he had all night.

The man in the stands was watching. His name is Eric Cairns, a former NHL defenceman and current director of player development for the Islanders. He’d been in St. Catharines all week, taking Ho-Sang out to dinner to talk about his progress and stopping in for a chat after each of his games, to debrief about what he’d just seen. They sat and talked for 45 minutes while the ushers made their rounds, this time with bags full of litter and empty pizza boxes. These interactions with authority haven’t always been easy for Ho-Sang, but tonight it’s a positive discussion; he played well and did the things the Islanders want him to do. He moved the puck quickly, backchecked hard through the neutral zone and even (gasp) blocked a shot. Of course, this isn’t always the case. There are nights when Ho-Sang tries to do too much, circling around the neutral zone with the puck on his stick for 15, 20, sometimes 30 seconds as he waits for the defence to make a mistake. He knows he’s good enough to get away with it and he’s also good enough to create a goal all by himself if he gets even a sliver of an opening. But when he’s circling around like that you can hear the fans in the seats groan and you can practically hear his coaches shouting at him from the bench to just move the freaking puck.

The Islanders are trying to find a balance between these two sides of their young prospect, and Ho-Sang is trying to find a balance within himself. “When I came into this league, I was a little shithead who was growing into a bigger shithead, basically,” he says. “I just wanted to hang high in the zone and chill for breakaways because I thought I was the best player on the team. I’ve definitely been tough to coach. But I’m definitely getting easier. I’m working on it. It’s patience. And it’s frustration. It’s tough adjusting. I’m trying to play a more complete game, be a more complete hockey player. We’ll see what happens next.”

wo hours to puck drop on a Saturday night in downtown St. Catharines, Ont. Red-blazered ushers make busy, lugging boxes of programs and giant plastic bags of popcorn back and forth through the Meridian Centre, home of the Niagara IceDogs. They edge toward the side of the concourse as teenage hockey players in T-shirts and hoodies stream past doing high knees and lunges, physically preparing for tonight’s game. The business of junior hockey, as usual.

wo hours to puck drop on a Saturday night in downtown St. Catharines, Ont. Red-blazered ushers make busy, lugging boxes of programs and giant plastic bags of popcorn back and forth through the Meridian Centre, home of the Niagara IceDogs. They edge toward the side of the concourse as teenage hockey players in T-shirts and hoodies stream past doing high knees and lunges, physically preparing for tonight’s game. The business of junior hockey, as usual.

Almost Done!

Please confirm the information below before signing up.

{* #socialRegistrationForm_radio_2 *} {* socialRegistration_firstName *} {* socialRegistration_lastName *} {* socialRegistration_emailAddress *} {* socialRegistration_displayName *} By checking this box, I agree to the terms of service and privacy policy of Rogers Media.